Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Operation Pedro Pan and More

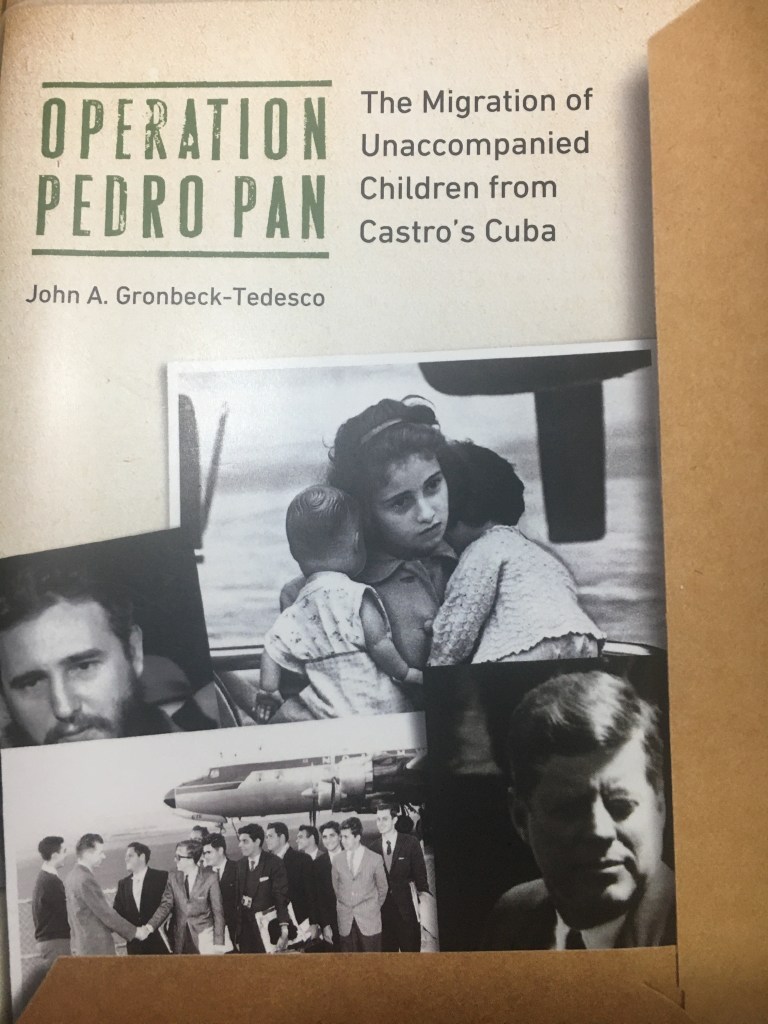

Review of Operation Pedro Pan The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba by John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, (2022), Potomac Books.[1]

In 2009, reading (for the second time) Carlos Eire’s award winning memoir Waiting for Snow In Havana I felt inspired to write my own recollection of my departure from Cuba as an unaccompanied minor, my arrival in the United States, and my first years in the country that received me with open arms. This project, which I started then and is still unfinished fifteen years later, led me to research Operation Pedro Pan everywhere that I could find information. [2] It was then that I connected for the first time with Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc., in Miami, joined the organization and served on its Board of Directors for 6 years. I enjoyed the comradery with such a large group of people who had all experienced being a Pedro Pan, and many of whom had a lot more knowledge of the nuts and bolts of the Operation and of its history than I did.

Still interested in all things Pedro Pan, I attended in April of 2023 a presentation of Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba by John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco at “Books and Books” in Coral Gables. I arrived just as the program was starting and was lucky to find a seat – the room was filled to capacity. Afterwards, as I waited to have my copy of the book signed by the author I saw two other Pedro Pan acquaintances. There might have been more that I do not know or did not recognize, but it seemed that the majority of the people in the audience were not Pedro Pans. If that was the case I think it is indicative of how interest in the issue has spread to the general public and perhaps also symptomatic of “Politics of Exile Identity,” discussed in Chapter 15 of the book.

What I write here is my own personal assessment of the work. In no way do I intend to represent the thinking of any of the various organizations that have been formed to remember the experience and honor the many dedicated people that made it possible.

Gronbeck-Tedesco excels in combining throughout his work the memories of ten Pedro Pans whom he interviewed with the archived historical records of Operation Pedro Pan and the other organizations involved. He also excels in presenting this exodus in the historical context of the Cold War and in the context of the development of child protection services in the United States from the late nineteenth century to the twentieth. (Chapter 9 “Cold War Childhood)

The issue of race appears throughout the work. In Chapter 5 “The Other Miami” Gronbeck-Tedesco includes lengthy interviews with two civil rights activists: psychology professor (now retired) Marvin Dunn who lived in Miami in the sixties when Cubans, including the Pedro Pan minors, started arriving by the thousands, and with T. Willard Fair, who became president of the Urban League of Greater Miami. This chapter stands out as one of the most important contributions of the book.[3]

Chapter 6 “Operation Pedro Pan in Cuba” centers on the question of how much was the CIA involved in convincing parents in Cuba to send their children to the United States as way of discrediting the Castro Revolution. This can be a hot button issue among Cubans, especially Pedro Pans. Rumors spread throughout the island that the Castro regime would take parents “patria potestad” (legal custody) thus taking away parents authority over their children. The charge of the Castro government was that the CIA promoted this rumor with a fake document that circulated among Cuban parents. As Gronbeck-Tedesco points out, some Cuban historians and others claim that the CIA was a lead player or the main orchestrator of OPP. About these claims, Gronbeck-Tadesco asserts: “But it turns out that definitive proof is not easy to come by; incontrovertible documentation is lacking.” [4]

When this issue comes up, I remember a letter written to me by my Mom, Augusta Mulkay de Muller, from Cuba, when I was already in the United States. She wrote it on the second anniversary of the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion. Right after the Invasion my brother Alejandro, age 15, was detained by the Castro police for ten days. She is remembering that event and how she reacted to it. This was no rumor.

“Two years ago, I had my children with me while wanting, or rather, trying to hide them from the clutches of evil, who finally managed to capture my young Alejandro. So was the beginning of the sprawl of our family, to which I agreed, and with some relief gave you and your brothers permission to leave all of this. You, so young still, when you needed me the most; the oldest, who realized the futility of remaining here.

…

“I am solely responsible for the separation and departure of all of you.

“In those difficult moments, my intention was to distance all of you from the great danger that awaited us; and deliver you from suffering – the suffering that this hateful regime has imposed on the Cuban people through force and terror.

“I do not regret what I did; although I must confess that I never thought it would take so long to get rid of this oppressive yoke, or that we would be separated for so long. If your return to us proves to be long to wait, we are prepared to leave here and go to be reunited with you, as we had planned, and which the course of history has ruined. God only knows why.”

The danger posed to us as minors was not a figment of the CIA’s imagination. My Mom’s decision was not a result of a falsified document. It was a response to a real event.

My mom and my dad, Carlos Muller, arrived in Miami in June of 1964, through a third country. Although they never returned to Cuba, they never expressed any opposition to us returning there. Unfortunately this can be another hot-button issue among Cubans and Pedro Pans in particular. This brings me to Chapter 16 “The Return” where Gronbeck-Tadesco favorably reports on the trips back to Cuba that some of the Pedro Pans that he interviewed have taken. He also mentions the animosity that some Miami Cubans manifest when they find out that a Cuban or a Pedro Pan has visited Cuba. Personally I find this judgmental attitude most unfortunate and undemocratic.

The decision to return to Cuba is a purely personal one. My two older brothers visited Cuba many times while our parents were still alive. My parents never objected. For many years I refused the idea of visiting Cuba but always understood that people’s circumstances varied and for some it was a good thing to return to the island.

Although I might never physically return to Cuba, I feel that I have returned in many ways. Since I do not reside in Miami, each time I visit there I feel I am back in Cuba. I have enjoyed reading accounts of visits to Cuba by various Cuban writers and also American writers and each has taken me back to Cuba. I have a collection of letters written by my parents and my brother, Francisco Javier, while they were still in Cuba, and even some I wrote myself during my last year in the island. Reading them I return to the Cuba that was.

I have also met with Cubans who left Cuba many years after I did. Talking with them I learn much of what transpired after I left. I have also talked with Cubans who still live on the island and visit the United States. Talking with them I return to the Cuba of today.

I must admit that Chapter 11 “Abuse” was the hardest to read. I have known about the abuse that some of the Pedro Pan minors suffered. I have no words to express the grief and regret. This happens also to be the shortest chapter in the book, perhaps indicative that, although of utmost importance, in comparison with everything else that went on during those years, the number of cases is small. In Chapter 15, “The Politics of Exile Identity”, Gronbeck-Tedesco includes comments made in an interview and email correspondence with Pedro Pan Pury Lopez Santiago:

“While she knows some suffered abuses, she point out that abuses of all kinds have occurred in foster homes and orphanages, and Operation Pedro Pan was no exception. She has a friend whose brother was a Pedro Pan and ended up in a halfway house. But she is convinced that the United States and the Catholic Church did the best they could to care for thousands of children.”[5]

I agree with Lopez Santiago.

I am amazed at the amount of research Gronbeck-Tedesco put into this work. In an interview with Tony Leal, which took place on the same day he spoke at “Books and Books” he stated that it took him seven years to write the book. [6] This is well evidenced in the numerous endnotes for the introduction and for each of the sixteen chapters and conclusion. The vast documentation that he has amassed in one volume may very well serve others interested in an in depth study of Operation Pedro Pan. A bibliography, which is not included, would facilitate the work of future writers interested in such an undertaking.

Besides being painstakingly researched, the book is also good literature. I appreciate his use of metaphor in the title of some of the chapters. For example, using air travel terms for Chapter 1, “TAKEOFF” and 2 “LANDING”. In addition the author manages to connect each of the well-crafted chapters in such a way that as one finishes reading each, one is almost compelled to continue on to the next. His writing style certainly makes it enjoyable to read this monumental work. Even if one does not agree with everything presented I think his work can and should be used by individuals and by groups to further our understanding and appreciation of Operation Pedro Pan.

Personally, I anticipate it might take me seven years to fully comprehend Gronbeck-Tedesco’s book.

[1] This review was first published in El Ignaciano, June 2024, www.elignaciano.com

[2] In a nutshell, Operation Pedro Pan can be described as the transport from Cuba and care in the United States of unaccompanied Cuban children fleeing communism from December of 1960 to October of 1962. The program which at its start envisioned the participation of some 200 children grew to unimaginable proportions to more than 14,000 when it ended. About a little over half of the children that arrived had no relatives or friends with whom to stay and for this reason the Unaccompanied Cuban Children’s Program that would care for them started almost simultaneously with the transporting part of the effort and lasted until 1981.

[3] A good follow up reading to this chapter would be Ricardo E. Gonzalez Zayas, Black Pedro Pan, Alexandria Library Publishing House, Miami, 2021.

[4] John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba, Potomac Press, p.89.

[5] Gronbeck-Tedesco, p.187.

[6] ¿Qué es Operación Pedro Pan? (Conversando a fondo – Episodio 9) (youtube.com) 01:35 – Interview with John Gronbeck-Tedesco, autor del libro “Operation Pedro Pan, the Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Cuba”. 21:23 – Interview with Celia Suárez, Pedro Pan 41:00 – Interview with Eloísa Echazábal, Pedro Pan.

as it happened through the years the parents did loose the “legal rights to their children “ with out actually signing a law as such.

some examples:

have all schools been run by the government and a requirement to send children to barracks at any place in the island, without been notified where, to be able to go to school. Barracks were conditions were very unheathy and the worst of food provided. Parents lacking a transportation system to visit or be able to go take food they could find to their children once in a while. A system where religious freedom was not allowed or else action taken against student and families. Only one place or choice given by the government for medical assistant even though called free. Careers only chosen by the government!

Think about it. Would we put up with that for our children? Isn’t that loosing legal rights of your children?

LikeLike

That is correct. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike