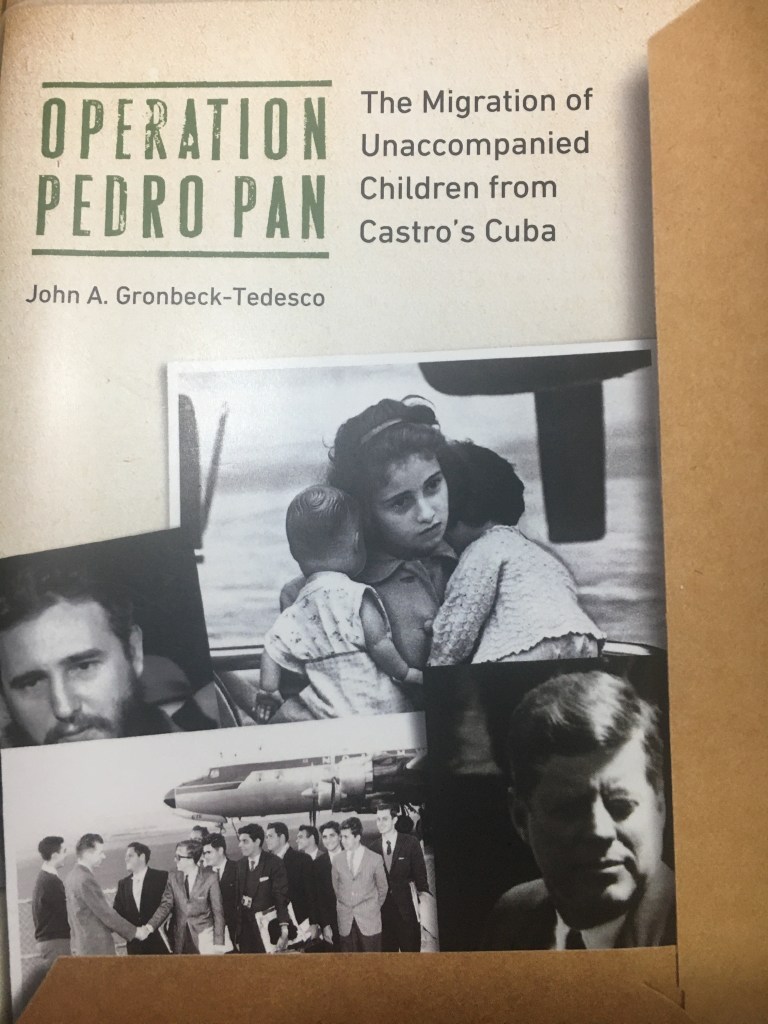

Review of Operation Pedro Pan The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba by John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, (2022), Potomac Books.[1]

In 2009, reading (for the second time) Carlos Eire’s award winning memoir Waiting for Snow In Havana I felt inspired to write my own recollection of my departure from Cuba as an unaccompanied minor, my arrival in the United States, and my first years in the country that received me with open arms. This project, which I started then and is still unfinished fifteen years later, led me to research Operation Pedro Pan everywhere that I could find information. [2] It was then that I connected for the first time with Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc., in Miami, joined the organization and served on its Board of Directors for 6 years. I enjoyed the comradery with such a large group of people who had all experienced being a Pedro Pan, and many of whom had a lot more knowledge of the nuts and bolts of the Operation and of its history than I did.

Still interested in all things Pedro Pan, I attended in April of 2023 a presentation of Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba by John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco at “Books and Books” in Coral Gables. I arrived just as the program was starting and was lucky to find a seat – the room was filled to capacity. Afterwards, as I waited to have my copy of the book signed by the author I saw two other Pedro Pan acquaintances. There might have been more that I do not know or did not recognize, but it seemed that the majority of the people in the audience were not Pedro Pans. If that was the case I think it is indicative of how interest in the issue has spread to the general public and perhaps also symptomatic of “Politics of Exile Identity,” discussed in Chapter 15 of the book.

What I write here is my own personal assessment of the work. In no way do I intend to represent the thinking of any of the various organizations that have been formed to remember the experience and honor the many dedicated people that made it possible.

Gronbeck-Tedesco excels in combining throughout his work the memories of ten Pedro Pans whom he interviewed with the archived historical records of Operation Pedro Pan and the other organizations involved. He also excels in presenting this exodus in the historical context of the Cold War and in the context of the development of child protection services in the United States from the late nineteenth century to the twentieth. (Chapter 9 “Cold War Childhood)

The issue of race appears throughout the work. In Chapter 5 “The Other Miami” Gronbeck-Tedesco includes lengthy interviews with two civil rights activists: psychology professor (now retired) Marvin Dunn who lived in Miami in the sixties when Cubans, including the Pedro Pan minors, started arriving by the thousands, and with T. Willard Fair, who became president of the Urban League of Greater Miami. This chapter stands out as one of the most important contributions of the book.[3]

Chapter 6 “Operation Pedro Pan in Cuba” centers on the question of how much was the CIA involved in convincing parents in Cuba to send their children to the United States as way of discrediting the Castro Revolution. This can be a hot button issue among Cubans, especially Pedro Pans. Rumors spread throughout the island that the Castro regime would take parents “patria potestad” (legal custody) thus taking away parents authority over their children. The charge of the Castro government was that the CIA promoted this rumor with a fake document that circulated among Cuban parents. As Gronbeck-Tedesco points out, some Cuban historians and others claim that the CIA was a lead player or the main orchestrator of OPP. About these claims, Gronbeck-Tadesco asserts: “But it turns out that definitive proof is not easy to come by; incontrovertible documentation is lacking.” [4]

When this issue comes up, I remember a letter written to me by my Mom, Augusta Mulkay de Muller, from Cuba, when I was already in the United States. She wrote it on the second anniversary of the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion. Right after the Invasion my brother Alejandro, age 15, was detained by the Castro police for ten days. She is remembering that event and how she reacted to it. This was no rumor.

“Two years ago, I had my children with me while wanting, or rather, trying to hide them from the clutches of evil, who finally managed to capture my young Alejandro. So was the beginning of the sprawl of our family, to which I agreed, and with some relief gave you and your brothers permission to leave all of this. You, so young still, when you needed me the most; the oldest, who realized the futility of remaining here.

…

“I am solely responsible for the separation and departure of all of you.

“In those difficult moments, my intention was to distance all of you from the great danger that awaited us; and deliver you from suffering – the suffering that this hateful regime has imposed on the Cuban people through force and terror.

“I do not regret what I did; although I must confess that I never thought it would take so long to get rid of this oppressive yoke, or that we would be separated for so long. If your return to us proves to be long to wait, we are prepared to leave here and go to be reunited with you, as we had planned, and which the course of history has ruined. God only knows why.”

The danger posed to us as minors was not a figment of the CIA’s imagination. My Mom’s decision was not a result of a falsified document. It was a response to a real event.

My mom and my dad, Carlos Muller, arrived in Miami in June of 1964, through a third country. Although they never returned to Cuba, they never expressed any opposition to us returning there. Unfortunately this can be another hot-button issue among Cubans and Pedro Pans in particular. This brings me to Chapter 16 “The Return” where Gronbeck-Tadesco favorably reports on the trips back to Cuba that some of the Pedro Pans that he interviewed have taken. He also mentions the animosity that some Miami Cubans manifest when they find out that a Cuban or a Pedro Pan has visited Cuba. Personally I find this judgmental attitude most unfortunate and undemocratic.

The decision to return to Cuba is a purely personal one. My two older brothers visited Cuba many times while our parents were still alive. My parents never objected. For many years I refused the idea of visiting Cuba but always understood that people’s circumstances varied and for some it was a good thing to return to the island.

Although I might never physically return to Cuba, I feel that I have returned in many ways. Since I do not reside in Miami, each time I visit there I feel I am back in Cuba. I have enjoyed reading accounts of visits to Cuba by various Cuban writers and also American writers and each has taken me back to Cuba. I have a collection of letters written by my parents and my brother, Francisco Javier, while they were still in Cuba, and even some I wrote myself during my last year in the island. Reading them I return to the Cuba that was.

I have also met with Cubans who left Cuba many years after I did. Talking with them I learn much of what transpired after I left. I have also talked with Cubans who still live on the island and visit the United States. Talking with them I return to the Cuba of today.

I must admit that Chapter 11 “Abuse” was the hardest to read. I have known about the abuse that some of the Pedro Pan minors suffered. I have no words to express the grief and regret. This happens also to be the shortest chapter in the book, perhaps indicative that, although of utmost importance, in comparison with everything else that went on during those years, the number of cases is small. In Chapter 15, “The Politics of Exile Identity”, Gronbeck-Tedesco includes comments made in an interview and email correspondence with Pedro Pan Pury Lopez Santiago:

“While she knows some suffered abuses, she point out that abuses of all kinds have occurred in foster homes and orphanages, and Operation Pedro Pan was no exception. She has a friend whose brother was a Pedro Pan and ended up in a halfway house. But she is convinced that the United States and the Catholic Church did the best they could to care for thousands of children.”[5]

I agree with Lopez Santiago.

I am amazed at the amount of research Gronbeck-Tedesco put into this work. In an interview with Tony Leal, which took place on the same day he spoke at “Books and Books” he stated that it took him seven years to write the book. [6] This is well evidenced in the numerous endnotes for the introduction and for each of the sixteen chapters and conclusion. The vast documentation that he has amassed in one volume may very well serve others interested in an in depth study of Operation Pedro Pan. A bibliography, which is not included, would facilitate the work of future writers interested in such an undertaking.

Besides being painstakingly researched, the book is also good literature. I appreciate his use of metaphor in the title of some of the chapters. For example, using air travel terms for Chapter 1, “TAKEOFF” and 2 “LANDING”. In addition the author manages to connect each of the well-crafted chapters in such a way that as one finishes reading each, one is almost compelled to continue on to the next. His writing style certainly makes it enjoyable to read this monumental work. Even if one does not agree with everything presented I think his work can and should be used by individuals and by groups to further our understanding and appreciation of Operation Pedro Pan.

Personally, I anticipate it might take me seven years to fully comprehend Gronbeck-Tedesco’s book.

[1] This review was first published in El Ignaciano, June 2024, www.elignaciano.com

[2] In a nutshell, Operation Pedro Pan can be described as the transport from Cuba and care in the United States of unaccompanied Cuban children fleeing communism from December of 1960 to October of 1962. The program which at its start envisioned the participation of some 200 children grew to unimaginable proportions to more than 14,000 when it ended. About a little over half of the children that arrived had no relatives or friends with whom to stay and for this reason the Unaccompanied Cuban Children’s Program that would care for them started almost simultaneously with the transporting part of the effort and lasted until 1981.

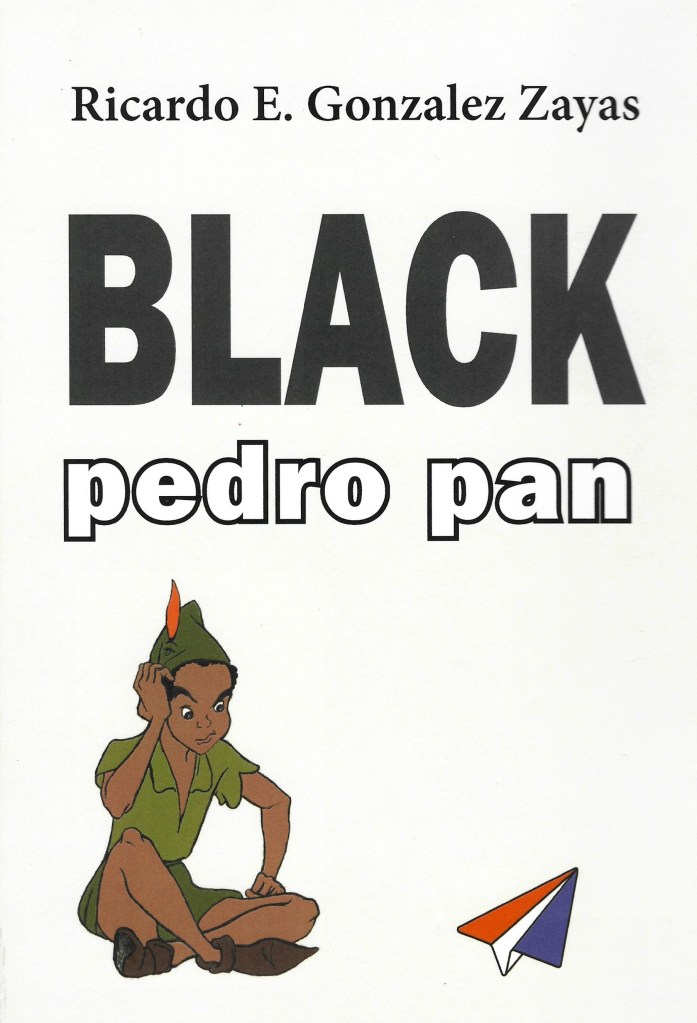

[3] A good follow up reading to this chapter would be Ricardo E. Gonzalez Zayas, Black Pedro Pan, Alexandria Library Publishing House, Miami, 2021.

[4] John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco, Operation Pedro Pan. The Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Castro’s Cuba, Potomac Press, p.89.

[5] Gronbeck-Tedesco, p.187.

[6] ¿Qué es Operación Pedro Pan? (Conversando a fondo – Episodio 9) (youtube.com) 01:35 – Interview with John Gronbeck-Tedesco, autor del libro “Operation Pedro Pan, the Migration of Unaccompanied Children from Cuba”. 21:23 – Interview with Celia Suárez, Pedro Pan 41:00 – Interview with Eloísa Echazábal, Pedro Pan.

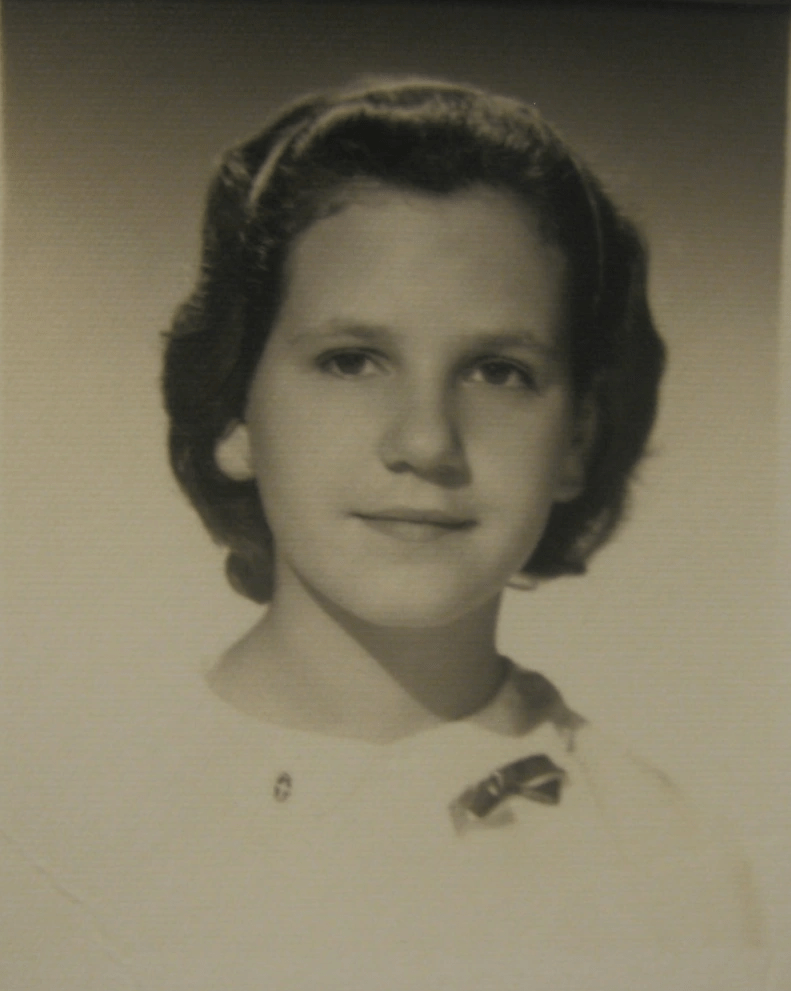

Desperté a las 6 de la mañana ese 4 de julio de 1961.

Recuerdo haber regado unas maticas de frijoles negros que hacía unas semanas había sembrado en una maceta redonda de barro carmelita, ancha pero no muy alta. Le pedí a mis padres, Carlos y Augusta, que me la cuidaran.

Ese día terminamos de empacar mi maleta. Recuerdo que mami incluyó un sweater rosado y una chaqueta dorada de vinilo. (Aunque era el mes de julio, me iba para el norte y tenía que tener abrigos para protegerme del frio.) Tengo que haberme despedido de mis hermanos Francisco Javier y Alejandro. Cuando les he preguntado muchas décadas después ellos me dicen que no se recuerdan. Mi hermano Carlos Alberto, el mayor de todos, ya estaba casado y no vivía en el apartamento del tercer piso del edificio de Miramar donde residíamos con nuestros padres.

El día antes me había enterado que me habían dado una visa waiver. En palabras de mi mamá, que oigo todavía dentro de mi como un eco del pasado “conseguida a través de eso que llaman Operación Pedro Pan.” He contado esto a algunas personas que me han comentado que es imposible que mami me hubiera dicho eso, pues ese nombre era un secreto y nadie lo conocía. Mi respuesta es, sí, era secreto para la prensa, para el público, para la mayor parte de las personas. Pero mi mamá lo conocía y me lo dijo. Tal vez porque en Cuba, y en cualquier país, es difícil guardar en secreto los secretos.

Cuando mami me anunció que me iba en el ferry para los Estados Unidos, yo estaba en casa de unos vecinos, quienes me habían ofrecido regalarme un conejito blanco y mis padres me habían dado permiso para tenerlo.

Desde finales de marzo, o tal vez principios de abril de ese año, yo había dejado de ir a la escuela. Ya casi todas mis amigas del Colegio de las Ursulinas se habían ido de Cuba. Extrañaba a mis compañeras y al colegio, que estaba cerrado porque el gobierno había intervenido todas las escuelas privadas y había cerrado hasta las públicas para cambiar el programa de educación en toda la isla. En ese aburrimiento y soledad, las maticas de frijoles me entretenían y el conejito me daría compañía. Los tuve que dejar.

Por supuesto, dejar atrás a mis padres y a mis tres hermanos fue lo más difícil. También el dejar a Cuba. El ferry J. R. Parrott originalmente cargaba trenes llenos de mercancía y ahora, después de la ruptura de relaciones diplomáticas entre Estados Unidos y Cuba, sólo transportaba pasajeros, incluyéndome a mi. Al salir el ferry del puerto de la Habana a eso de las doce del día, me quedé mirando el Castillo del Morro hasta que desapareció de mi vista. El plan era encontrarme en Miami con mi amiga Ofelia, y su familia quienes habían salido de Cuba un año antes y generosamente le habían ofrecido a mis padres el darme albergue hasta que pudiera regresar a Cuba – seguramente la estancia sería de no más de un año. Así todo, quería grabar en mi corazón la imagen del Morro que simbolizaba la patria donde nací y el único país que había conocido en mis trece años y medio de nacida.

El ferry llegó a West Palm Beach el 5 de julio al mediodía. Me dio la bienvenida a este país Elenita, una amiga de mi familia que vivía en esa ciudad West Palm Beach. Había un fuerte calor en el puerto y ella me ofreció una Coca Cola bien fría. Me la tomé entera y esto ayudó a quitarme la sed que tenía. (Afortunadamente los abrigos que mami me había insistido que llevara estaban guardados en la maleta.)

Una prima de ella, también llamada Elena,me llevó en automóvil al Northeast de Miami, a casa de unos familiares. Pasaría una semana antes de que me llevaran a casa de mi amiga.

Esa noche fui caminando con mis familiares a un centro comercial que quedaba cerca. Vi un Walgreens por primera vez. Entramos en una tienda similar al Woolworth que había en Cuba que llamábamos “tencén” (de “ten cent store”). Ahí vi por primera vez un bebedero que tenía un letrero que decía “Colored” y otro que decía “Whites” y también puertas de baños igualmente marcadas. Le pregunté a mis acompañantes que qué querían decir esos letreros y por qué estaban ahí. No recuerdo muy bien lo que me contestaron, pero los letreros se me quedaron grabados en mi memoria.

Tanto ha pasado y tanto ha cambiado en esos 62 años que han transcurrido. El plan de regresar a Cuba en un año, nunca se dio. Mi sueño de adolescente de educarme para poder regresar a Cuba y servir ahí quedó truncado. Los planes personales tuvieron que cambiar, tanto los importantes, como los insignificantes.

Tristemente, sin embargo, la situación en Cuba casi no ha cambiado en 62 años. Siguen saliendo de la isla cubanos desesperados porque las condiciones cada vez empeoran más. Siguen separándose las familias.

En los Estados Unidos, el país que me acogió, sí ha habido cambios en estos 62 años. Terminó la segregación explícita de la era de Jim Crow: no hay más letreros en los bebederos y en los baños, y han habido cambios en las leyes civiles. Aunque todavía queda mucho más por hacer, ha habido progreso. En “La Colina que Escalamos” la joven poetiza americana Amanda Gorman describe a los Estados Unidos como “una nación que no está quebrada/sino simplemente incompleta.” Si aplicáramos su bella poesía a Cuba le llamaríamos “La Colina que descendemos” y describiríamos a la isla como “una nación quebrada/cada vez más destruida.” Cuba en vez de progresar ha retrocedido.

Aunque no he regresado a Cuba ni de visita, regreso cuando leo o escucho los relatos de las personas que la han visitado en las diferentes décadas, en las fotos que ellos me han enseñado, en los libros escritos por personas que vivieron ahí mucho más años que yo, y sobre todo regreso cada vez que escucho a aquellos que siguen llegando.

También regreso a Cuba en mis recuerdos, especialmente en días como hoy al recordar mi salida: las maticas de frijoles negros en la maceta de barro y el conejito blanco.

________________

Doy gracias a Dios, y a todos los que han hecho posible el que haya podido vivir bien en esta gran nación, los Estados Unidos, mi país adoptivo. A la vez, me preocupa la situación de los miles y miles de personas que hoy día buscan salir de Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua y Haití bajo el nuevo programa de parole humanitaria de los Estados Unidos que admite a 30,000 personas de esos países cada mes. Ruego para que se haga todo lo posible por acelerar ese proceso.

Le deseo a cada uno de los que logren llegar la misma bienvenida y buen trato que recibí yo hace 62 años.

I woke up early on July 4, 1961.

I watered the black bean seedlings I had planted in a round clay pot a few weeks before. I asked my parents, Carlos and Augusta, to take care of them.

That day we finished packing my suitcase. I remember Mom insisted that I take a thick pink sweater and a yellow vinyl jacket. (Although this was July, I was travelling north and therefore I had to take them to protect me from the cold.) I must have said goodbye to my brothers Francisco Javier and Alejandro. When I have asked them decades after they tell me they don’t remember. My brother Carlos Alberto, the eldest, was already married and did not live with us in the third floor apartment of the building in Miramar, a suburb of La Habana, where we resided with our parents.

I had found out the day before that I had been granted a visa waiver. In the words of my Mom, which I still hear as an echo from the past, “conseguida a través de eso que llaman Operación Pedro Pan.” (“Obtained through what they call Operación Pedro Pan.) Some who have heard me say this have told me that it is impossible that my Mom would have said that because the name was a secret. I always reply, yes, it was secret for the press and for most of the general public. But my Mom knew it and she told me. Perhaps because in Cuba, and in any other country, it is difficult to keep such secrets secret.

When my Mom told me that I was leaving in the ferry for the United States, I was at our neighbor’s house. The neighbor had offered to give me a white bunny and my parents had given me permission to accept it.

Since the end of March of that year I had stopped attending school. Almost all my friends from the Colegio de las Ursulinas had left Cuba. (In Spanish “colegio” means “school” not college.) I missed my friends and the school which had been closed by the government as part of its complete revamping of the educational system in the island. In the midst of that boredom and loneliness the black bean seedlings kept me entertained and the white bunny would accompany me. I had to leave them.

Leaving my parents, my three brothers, and Cuba was the most difficult thing I had ever done. The J.R. Parrot ferry originally transported train cars filled with merchandise and now that the United States had severed diplomatic relations with Cuba, it only transported people. As the ferry left the port of La Habana at about noon, y gazed at the Morro Castle until it disappeared in the horizon. The plan was for me to meet my friend Ofelia and her family, who had left Cuba a year before, and stay with them for no more than a year. Nevertheless I wanted to have the image of the Morro seared in my memory for it represented the homeland where I had been born thirteen and a half years before.

The ferry arrived in West Palm Beach at noon on July 5th. Elenita, a friend of my family who now resided in that city, welcomed me at the port of Palm Beach. It was a hot day and she offered me a cold Coca Cola. I drank it all and it quenched my thirst. (Thank goodness the coats that my Mom had insisted I take were in the suitcase and not on me.)

Her cousin, also named Elena, drove me in her car to the Northeast section of Miami, to the home of some of my relatives. It would be a week before they were able to take me to my friend Ofelia’s house.

That evening my relatives took me for a walk to a nearby shopping center. I saw a Walgreens for the first time in my life. We then walked to a store similar to a Woolworth’s that we had in Habana. There I saw for the first time two water fountains, one with a sign that said “Colored” and the other with a sign that said “Whites.” I also saw similar signs on the bathrooms. I asked my relatives what the signs meant and why they were there. Although I don’t remember how they answered then, the signs were engraved in my memory.

So much has happened and so much has changed in these 62 years. The plan to return to Cuba in a year never happened. My adolescent dream of receiving an education and then return to Cuba to help there never came true. I had to change all my plans, the important as well as the insignificant ones.

Sadly, Cuba has not changed. Sixty two years later, there are still Cubans on the island desperate to emigrate because the conditions there worsen by the day. Families continue to become separated.

In the United States, the country that welcomed me, there have been changes in these 62 years. The Jim Crow laws changed and there have been changes in civil laws. There are no more signs separating Colored from Whites in bathrooms and water fountains. Although much remains to be improved, there has been change for the better. The nation has progressed. In “The Hill We Climb,” the American poet Amanda Gorman refers to the United States as “a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.” Paraphrasing the young poet laureate, a poem about Cuba would be called “The Hill We Descend” and we would refer to the island as “a broken nation, each time more destroyed.” Instead of progressing, Cuba has regressed.

Although I have never been back to Cuba, not even for a visit, I do “return” each time I hear the stories of people who have visited the island at different times throughout these six decades, when I see the photos they have taken, and when I read books by people who have lived there much longer than I did. I “return” each time I hear the stories of those who continue to arrive from the island.

I also return to Cuba in my memories, especially in days like today when I recall the day I left, and remember the black bean seedlings in the clay pot and the white bunny my neighbor had given me.

________________

I give thanks to God and to all who have made it possible for me to live and thrive in this great nation, the United States, my adoptive country. At the same time I am concerned about the desperate situation of the thousands and thousands of people who are trying to leave Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Haiti through the new humanitarian parole program from the US government. This program admits 30,000 people from those four countries each month.

I wish for each and every one of them that make it to this country the same welcoming and good treatment that I received 62 years ago.

As we do every 4th of July, my husband and I set up our American flag yesterday on the front of our house early in the morning. I was not as enthused about this ritual observance as I have been in years past. I did not say anything.

My enthusiasm for displaying the flag was down to about zero on a scale of one to ten. The problem is not the flag, but rather that in our current sociopolitical climate the flag is often used not to signify the nation that unites us but instead it is used to signify an ideology that divides.

In addition, instead of following established protocols for handling the flag with respect, many display it year round. I see faded and frayed flags, day in and day out. Although the official guidelines for displaying the flags are ignored, there are no penalties for disregarding them because of the First Amendment right of free speech. I find it ironic that the same President that wanted to punish flag burners with loss of citizenship and a year in jail saw nothing wrong with his flag bearing supporters breaching the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 to disrupt the peaceful transition of power.

Those thoughts were weighing heavily on me yesterday, a day which also has a special personal meaning for me, since that is the day I left Cuba, my country of birth, sixty one years ago. I left on the Joseph R. Parrot, a ferry that plied the waters from Havana to the Port of Palm Beach, a 24 hour journey. That makes today, July 5th, the 61st anniversary of my arriving in this country. That day marks the end of my life as a child and the beginning of my life as an adult, well, an almost-adult, since I was 13 years old but travelling alone. In my heart the celebration of American Independence and my migration experience are intertwined in a special way.

Trying to get my thoughts off the divisiveness that the American flag has come to signify in some quarters, I decided to look up the seal of the United States of America, which has inscribed on it the Latin phrase: E pluribus unum, meaning “from many, one.” Originally the phrase referred to the thirteen colonies that united to form one nation. As the nation’s history has evolved, the phrase has come to mean that our nation is made from many people of different origins united as one.

One of the first links that I found on my initial internet search led me to a book that was published in 2021 with the title Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants. The book has 43 full color portraits of immigrants and their stories. The author: George W. Bush. I read many of the comments written by people who have read it. While some, perhaps two or three readers blasted the author of the book and gave the book a 1 star rating, many more, including people who said they were not fans of the 43rd President, gave the book a 4 and 5 star ratings. I have not had a chance to read it but just finding about it today, made me feel good. This feeling came about not only because of my own immigrant experience, but also because of the welcoming spirit in which the book is written, captured in this statement by President Bush: “We must always be proud to welcome people as fellow Americans. Our new immigrants are just what they’ve always been – people willing to risk everything for the dream of freedom.”

On the 61st anniversary of my arrival in this country as an unaccompanied refugee child, I join in this welcoming of today’s new immigrants.

I sensed something unusual had happened when my Dad came to pick me up from school early in the afternoon on February 5, 1961. I was in the sixth grade at Colegio de las Ursulinas de Miramar. Normally at the end of the day I would walk home with my friend Ofelia. We were neighbors and lived a long block away from the school. As soon as I got in the car that afternoon my Dad said: “There was a shootout at the Parque Central today and your cousin Alberto was detained by the police.” My Dad looked worried and I realized that whatever had happened was something very serious. I, too, started to worry about Alberto.

My cousin Alberto Muller, who was 20 years old at the time, was a student at the University of Havana and was a member of the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (University Student Federation, known as FEU for its acronym in Spanish). He was also a member of the Agrupación Católica Universitaria, (Catholic University Group, known as ACU) an association of Catholic University students attending public institutions such as the Universidad de la Habana, and also private ones, such as the University of Villanova (Universidad de Villanueva) in Havana. Many of these students had been involved in actions against Dictator Batista and had eagerly cooperated with the Revolution after its triumph in January of 1959. Soon they began to realize that the Revolution was turning away from its promises of democracy and freedom.

In early 1960 the students found out that Anastas Mikoyan, a high ranking official of the Soviet Union, would be visiting Cuba. News reports of the 1956 brutal suppression of Soviet troops that suppressed the popular revolt against Soviet control in Hungary was still fresh in their memory – they were well versed in international affairs. Mikoyan’s presence in Cuba was an additional indicator for them that under Castro the Revolution was definitely turning into a dangerous path towards Marxist totalitarianism. Members of the student groups met several times to plan a peaceful demonstration protesting the Soviet official’s visit.

The students found out that on February 5th Mikoyan was to present a wreath of flowers in front of the statue of José Martí, the apostle of Cuban independence, at Havana’s Parque Central (Central Park). They decided to meet at the park and present a wreath of flowers representing the Cuban flag. Hundreds of students attended this peaceful protest. They carried signs saying: “Revolución Sí, Comunismo No” (Revolution, yes. Communism, no.) Another sign said: “Viva Fidel, Abajo el comunismo ruso.” (Long live Fidel, down with Russian communism.) The students were clearly not against the revolution itself, but against the communist infiltration of the revolution.

As the students arrived at Havana’s Parque Central, one of the military guards fired a shot into the air to discourage the public from approaching the statue. Other guards responded by doing the same and the sounds of the shots ricocheted on the tall buildings near the park. A physical battle ensued between the guards and the students. Both wreaths were torn to pieces. The students did not intend to destroy the Soviet’s wreath. All they intended to do was to place theirs next to it. Writing several years ago about this event, my cousin Alberto notes that the wreath that Mikoyan had placed by the statue had a hammer and sickle, which by this time had become a symbol of Soviet communism. The students’ wreath had the colors of the Cuban flag, representing Cuba’s freedom. 1

In his recently published memoir, Three Worlds. A Journey to Freedom, Antonio Garcia Crews, who was one of the organizers of the Parque Central protest, writes about his involvement in its planning. On his way to the park a policeman stopped his car because one of his passengers was throwing out fliers directing people to join the demonstration. The policeman ordered him to drive to the Police Station where he opened the trunk and saw the signs that they had made. As he and his four passengers were ushered into the station they heard the first shot fired by the authorities at El Parque Central – all the protestors were unarmed. During the course of the day other protesters were brought into the station. Twenty one students spent that night in jail. One of them was my cousin Alberto. They were released the next day. 2

Reflecting six decades later on the significance of the Parque Central protest Garcia Crews writes in Three Worlds: “I was 19 years old and still had a few months left to graduate in Economics from the University of Villanueva. I was already convinced that the so-called revolution that had “freed” the country was itself a dictatorship headed in the direction of implementing a dictatorship, worse than the previous one: a Communist dictatorship would guarantee Fidel Castro the absolute and permanent power he yearned for. This was only the beginning. In our case, there was no explanation to jail a group of peaceful and unarmed demonstrators.” 3

About a month later, under extreme pressure by the Castro regime, the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria expelled the leaders of the Parque Central protest from the University of Havana. That included my cousin Alberto. 4

Realizing that there was nothing left for them to do in Cuba, Alberto and several of the leaders of the student group at the Universidad de la Habana left the island. Some went to Latin America, many went to the United States. Antonio Garcia Crews finished his studies at Villanova University, Havana’s Catholic University, and immigrated to the United States to attend graduate school at the University of Chicago. Within a few months Alberto and a group of other student leaders founded in Miami the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil (Revolutionary Student Directorate) or DRE for its acronym in Spanish, or simply, Directorio.5 Alberto called Garcia Crews and met with him in New York. Garcia Crews decided to forgo his studies and joined the Directorio. Alberto, Garcia Crews and other of the student leaders returned to Cuba to join the underground fight against Castro. Alberto and Garcia Crews and many others of their student companions were arrested in 1961 and served long prison sentences in Cuba’s political prisons. Some lost their lives.

After their release from prison in the late 1970s Garcia Crews and Alberto were both able to immigrate separately to the United States where they raised their families while continuing to lead a life of dedicated service. Neither one of them has retired. Garcia Crews still practices as an immigration lawyer and Alberto still works as a journalist.

________________________

1 Alberto Muller, Retos del Periodismo,(The Challenges of Journalism)Ediciones Universal, 2008, 27-29.

2 Antonio Garcia Crews, Three Worlds A Journey to Freedom, Ediciones Universal, 2021, 42-43.

3 Garcia Crews, 43-44.

4 Alberto Müller: ‘Fuimos los primeros expulsados de la Universidad de La Habana bajo el comunismo’ (cubalibredigital.com) (We were the first to be expelled from the University of Havana under communism.) August 10, 2021.

5 Garcia Crews, 45-46

As summer ended in 1962 I rode alone on a Greyhound bus from Miami, Florida to Dallas, Texas. I was a 14 year old Cuban girl who had left Cuba the year before thanks to Operation Pedro Pan, a program that resettled unaccompanied Cuban children fleeing Castro’s communism. As we stopped at a bus station for a lunch break midway through the trip I noticed that all the black passengers stayed seated on the back of the bus. I asked why they were not getting off. “We are not allowed in the restaurant,” an older lady replied. I was extremely saddened when I heard this.

Unbeknownst to me, probably less than a year later, a fourteen year old Cuban boy, who had also left Cuba thanks to Operation Pedro Pan, found himself being told to seat in the back of a Miami city bus. Ricardo Gonzalez Zayas, one of a handful of black teenage boys staying at the Florida City shelter for unaccompanied Cuban children, narrates this incident in his memoir, Black Pedro Pan. He recalls that he had been given permission to ride a bus to visit a former neighbor from his hometown of El Cotorro, a municipality in the province of Havana, who had recently arrived in Miami and was residing near the shelter. When he got on the bus, the bus driver, a “red-faced white man” told him something that he did not understand since he was just starting to learn English. He stood in place until he heard the voice of another bus rider who translated for him the command of the bus driver. “At the time, I could not process what had happened but soon I learned that I had, for the first time, come face-to-face with the naked, ugly mug of racism as it was practiced in Miami and the United States in 1963.” (p. 55)

As a white Cuban, I had witnessed the ugly face of racism. As a black Cuban, Ricardo experienced it in his own person. He is right on the mark when he states that “Black Cuban exile is not the same as white Cuban exile…” (p.13). This point is brought out throughout the book. One of the most dramatic instances occurred in 1966 after his parents arrived in Miami. He went with them to rent an apartment in Little Havana at a building managed by a Cuban exile. A friend who knew the manager had told them that there was an apartment available for them. When the manager saw the color of their skin he refused to rent them the apartment. Ricardo was aware that recent laws had prohibited discrimination in housing. He confronted the manager and informed him he would call the authorities if he did not let them rent the unoccupied apartment. He reluctantly allowed them to rent an apartment in the building.

Ricardo writes: “After that regrettable experience it became clear that, going forward, our lives would be shaped in unforeseen and unpredictable ways by the color of our skin and, more importantly, we should be alert to that sort of prejudice even from those who, like us, had fled the island supposedly running away from injustice.” (p.73)

After pointing out the different exile experience that Ricardo had because of his race, I also have to note that in all other aspects his experience was the same as that of all the other unaccompanied minors that participated in Operation Pedro Pan. I enjoyed reading about his extended family in Cuba and perfectly identify with the experience of the family division – the “cracks”– that the Revolution caused. We can feel the anguish his parents felt in making the decision to send him to the United States, and it reminds us of the anguish our own parents felt. Of course, in his case, his parents were aware of the racial injustice that prevailed in the United States and this made their decision much more difficult to make. As many of our parents, his were certain that the separation would be only for a short period of time.

I loved reading his description in the “fish bowl” at the Rancho Boyeros airport, the room that separated by a thick glass wall the passengers who were waiting to board the airplane from the relatives that were staying on the island. One of the most poignant narratives in the book is that of his arrival at the Miami airport with the two sisters and little brother from a family of his hometown that his parents had happened to meet at Rancho Boyeros that same morning. Expressing how he felt during his first few days in Miami Ricardo writes:

“The reality of my new life and new surroundings, combined with the tremendous sense of separation from my parents and everyone and everything I knew, hit me with the force of a sledgehammer. I missed my old life terribly…. I wanted to go back to Cuba. ” (p. 49)

I felt the force of that sledgehammer on my first night in the United States – and I am sure many other Pedro Pan children felt the same way.

As time passed, with the help of the staff at the shelter and the new friendships he made Ricardo gradually assimilated into his new life. He reunited with his parents in Miami while he was attending high school. He graduated from Biscayne College, also in Miami and worked with the Travelers Insurance Company for many years. He returned to Miami and worked for the municipal government. He is now retired and lives in northeast Florida with his wife Mariana.

Gonzalez Zayas has travelled to Cuba many times, initially to visit his large extended family that stayed behind. I thoroughly enjoyed his detailed accounts of each of his visits. They give a glimpse of what life is like in communist Cuba. It also gives us a close up look of what black Cubans have experienced throughout the different stages of the Revolution.

I was fortunate to attend a book presentation of Black Pedro Pan at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora in Miami on September 3. The large room was packed with friends of Ricardo from the camps, from high school, and from many other organizations. As each spoke during the Q & A session the audience could sense the strong bonds of friendship that still exists between them and Ricardo. In answer to a question he explained that he does not name the persons in his book, or the places that discriminated against him because he is not writing to accuse anyone in particular. His purpose is not to throw stones and get revenge. His purpose is a noble one. Recognizing the wrongs done is necessary to heal the wounds they cause lest they fester in the dark. This is a necessary step for the healing of our societies from the evil of racism – not just in the United States, but also in Cuba.

Black Pedro Pan is a beautifully written book. It is easy to read. I found myself pausing often to feel fully the many poignant moments and at other times to reflect on Ricardo’s wisdom. Of course this book is of special interest to all who participated in Operation Pedro Pan including their counsellors, teachers and house parents and to Cubans who arrived in Miami in the sixties and subsequent decades. It should also be of interest to white and black Americans who have interacted with the Cuban community whether in the United States or in Cuba.

Above all Black Pedro Pan should be of interest to those who are dedicated to fostering racial justice in the continent or on the island. In today’s world that should include us all.

I can imagine the radiance in Carlos’ face on the day he bought the engagement ring for Augusta.

A young man of 25 years, Carlos had met Augusta only a few months earlier. She had just turned 24. They had met at the office where they both worked and they immediately felt attracted to each other.

The ring, made of platinum on the outside and gold inside, was covered with tiny sparkling simulated diamonds. He had the date of their engagement engraved inside: May 5, 1934. He paid 8 pesos for it at a jewelry shop in Havana. A fortune for him, considering his salary was 95 pesos a month. They were married a few months later, and the ring became her wedding ring.

The silver ring witnessed the birth of their first two sons, Carlos Alberto, born eleven months later and Francisco Javier, born in 1939.

Augusta had obtained her kindergarten teacher certificate before meeting Carlos, but the governing party had changed and the new government had declared invalid all the diplomas earned the year Augusta had completed her training. In 1936 Carlos took a job at Minas de Matahambre, a copper mine in Cuba’s easternmost province. Augusta stayed behind in Havana to complete a three-month-course that would revalidate her teaching certificate. The thin ring remained on her finger, a symbol of the love that endured across the miles that separated them.

Five months after Francisco Javier was born, Augusta was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Two long hospital stays separated Augusta and Carlos again. During her confinement at the “Sanatorio la Esperanza,” a sanatorium in the outskirts of Havana, Augusta met many other married women whose husbands had abandoned them because of their seclusion in the hospital. She then realized the depth and the strength of Carlos’ commitment to her. I can imagine her looking at the ring on her finger during those lonely days. I can imagine a smile forming on her face as the ring reminded her of the love it signified.

After several years of struggling with the disease and trying all available remedies for it, Augusta was finally cured. Shortly after that, Carlos became ill with pneumonia. An adverse reaction to an injection that was part of the treatment to cure him, brought him close to death. In fact, his brother and father, both doctors, declared him dead. A third doctor, a neighbor and friend of the family, realized that he was not dead and ordered that he be given intravenous feeding since he was dehydrating rapidly. Augusta and other relatives sat by his bed day and night to make sure that the I.V. was flowing properly. I can imagine her clutching to the ring on her finger throughout that long watch. Carlos recovered and eventually healed completely.

The ring was present at the birth of a third son, Alejandro, in 1945, and two years later, my own. “This one is different,” said the nurse that had assisted at the birth of their three sons, as she announced the gender of their fourth and last child.

When I was a little girl my Mom was a Kindergarten teacher and also a student at the University of Havana completing her degree in Education. Sometimes she took me with her to her classes. I remember seeing the silver ring as she clutched on to me to make sure I would not fall as we went up the eighty eight step stairway at the main entrance of the University.

I had just celebrated my eleventh birthday when Fidel Castro made his triumphant entry into Havana on January of 1959. As I have written before, my family celebrated what seemed to be a victory for freedom, justice and democracy. I celebrated with them and so did my mother. Her ring, glittering in her sun bathed hand, cheered Castro’s triumph.

The months and years that followed brought one disappointment after another. Not only did the Revolution not fulfill its promise. It brought in a reign of terror. In 1961 my Mom and Dad had to make the most difficult decision of sending their two minor children away and of encouraging their two adult children to leave the country. They harbored the hope that the Castro regime would come to an end. When that hope was shattered they decided to emigrate. Three years later the regime allowed them to leave.

My Mom did not include any valuables in her suitcase when she packed for her trip. She returned to her Mom, my grandmother Antonia, a cherished gold watch she had given her as a gift. She was sure the custom agents at the Rancho Boyeros Airport in Havana would take it away. She kept her silver ring on her finger, hoping the custom agents would let her take it. As she went through customs an officer saw her silver ring and asked her to take it off and give it to him. “You will get it back when you return in 29 days,” he said.

My Mom knew she was not going to return. After we reunited in the United States she spoke to me repeatedly of the sadness she felt as she surrendered the silver ring. “The ring was worth very little,” she said. “The memories it held for me made it irreplaceable.” The ring had been her constant companion throughout the joys and the griefs she had shared with my father in their years of marriage. It had witnessed births. It had survived illnesses, involuntary separations, and political upheavals. It did not survive Castro’s revolution.

Shortly after their arrival in Miami my parents celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary. They celebrated many more anniversaries with family, extended family and friends. In their old age, when they were frail, their health failing and their hair had turned as white as the gown and suit they had worn on their wedding day, we marked their anniversaries by visiting them at their home in Miami.

On May 23 of 1999, after my Dad had been feeling ill for over a week, I drove to their house to pick him up to take him to the hospital. As we were leaving out the door he stopped and turned around. “I have to say good bye to Augusta,” he said. She was sitting on a chair in the living room. He approached her and gave her a kiss. We left. My Dad died at the hospital 6 days later. They would have celebrated 65 years of marriage on August 26 of that year.

Although the silver ring Carlos had given to Augusta 65 years before had not survived the Revolution, the love the ring symbolized endured until death made them part. Their love won. I feel deeply grateful for that.

__________________________________________________________________

This was published originally as “Anillo de Compromiso (Engagement Ring)” in La Voz Católica in November of 1989. This is a revised and updated version.

On July 22, 1961, two and a half weeks after my arrival in Miami, I visited my uncle Panchito and Aunt Sara at her niece Graciela’s house. As the July sun was starting to come down on the horizon uncle Panchito and the other family members took out the porch chairs and set them on the grass alongside the front walkway, forming two rows facing each other so they could talk and leaving the cement path free so others could pass by.

I had just gone back inside the house when I heard a commotion outside. I heard a very familiar voice say: “Soy yo, Alejandro. No me reconocen?” (“It’s me, Alejandro. Don’t you recognize me?”) I could not believe my ears. My brother Alejandro in Miami? No one had called to say that he was arriving. In disbelief I started to rush outside as he was walking in. “Alejandro, sí, es Alejandro. Cómo llegaste aquí?” (“Alejandro! Yes, it is Alejandro. How did you get here?”) We hugged each other.

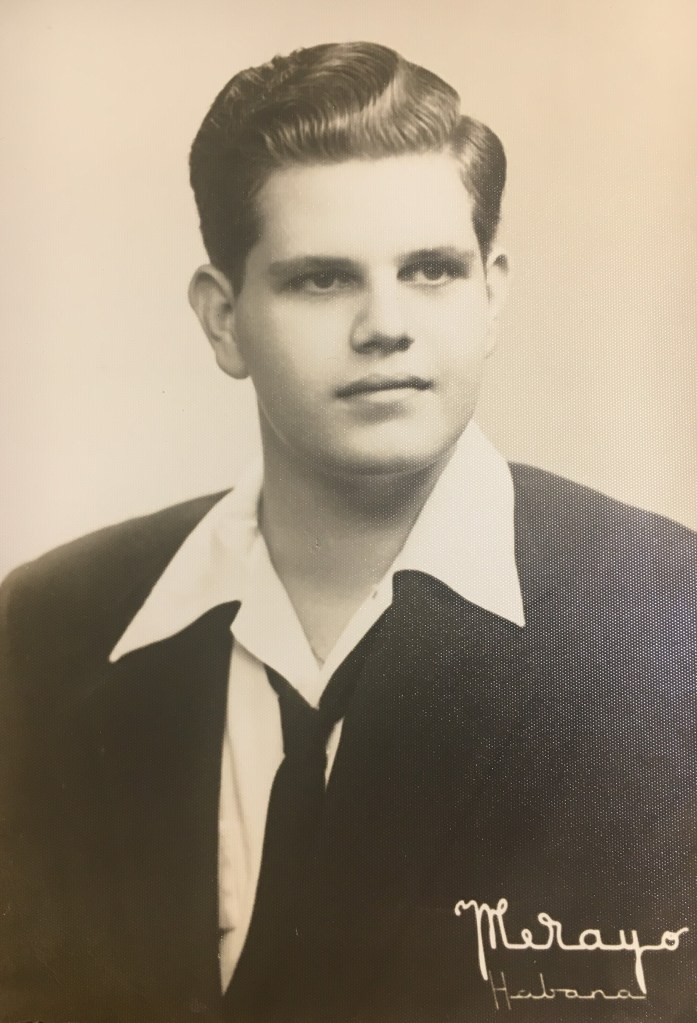

My uncle Panchito and my aunt Sara, and all the other relatives did not recognize him initially because they had not seen him for about two years. Alejandro, who had been a chubby boy, famous within the family and close circle of friends for being a big eater, had slimmed down and had grown to be six feet tall. Now 15, boy Alejandro had turned into handsome young man Alejandro.

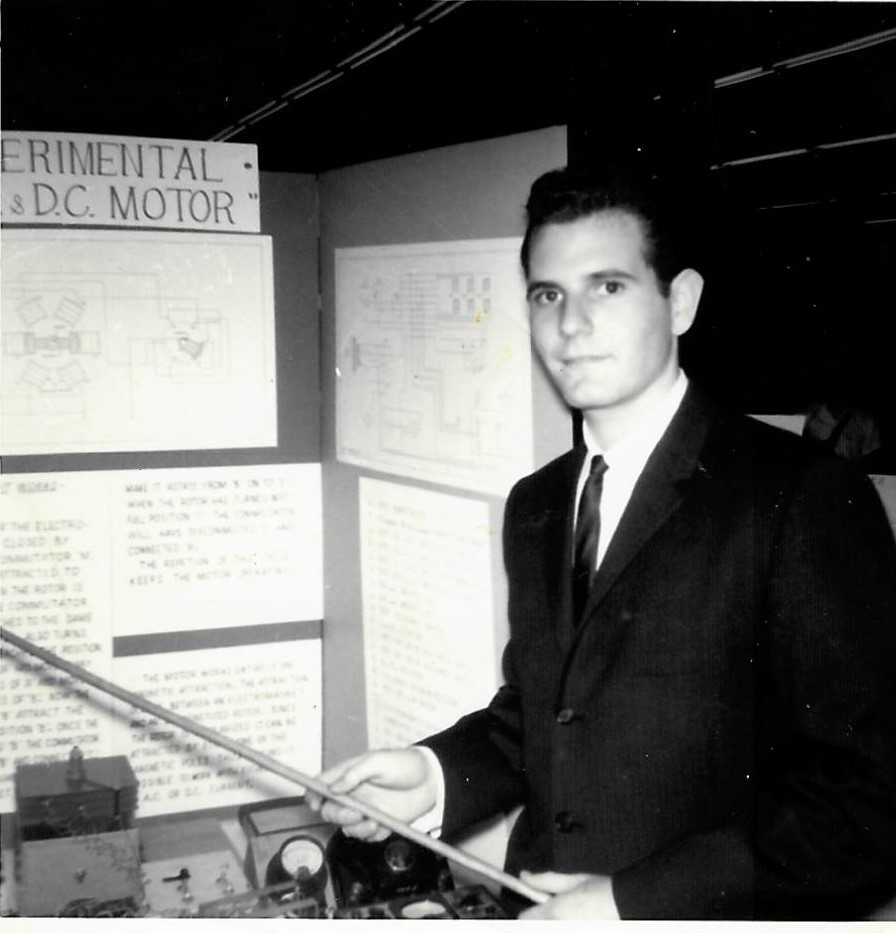

Alejandro had arrived at the Miami Airport on Thursday July 20th as an unaccompanied child, thanks to a visa waiver from Operation Pedro Pan. He had spent two days at the camp in Kendall where many unaccompanied Cuban children resided at the time. Someone had the kindness to drive him to the Reynaldo’s so he could visit with the family.

The great joy of seeing my brother again soon turned into sadness when I was told that he would only be with us for the weekend. Nevertheless, we did the best we could under the circumstances. We walked to the same shopping center that I had walked to on the day I had arrived in Miami. We ate dinner at the Reynaldo’s, where we both spent the weekend. We must have gone to church on Sunday, and I remember going to a movie with him that afternoon. Someone picked him up on Monday, and he was transferred to St. Vincent’s Villa, a former orphanage in Fort Wayne, Indiana, that was then housing unaccompanied Cuban boys.1 When the new school year began, Alejandro started to attend Central Catholic High School. 2

In 1963, when he was a senior, he entered a project in the Indiana Regional Science Fair and won first place in Physics. This led to a one-year scholarship and Indiana Institute of Technology. He attended Indiana Tech for a year and a half, but ended up graduating from Purdue University several years later.

Our parents were still in Cuba when Alejandro won first place at the Science Fair and they were very happy when they heard the news. My Dad raved about him in the letters that he wrote to the family.

In June of 1964 our parents arrived in Florida. Alejandro rode a Greyhound bus from Fort Wayne to Miami to see them. He considered staying with them, to help them out, but after some advice from the owner of a boat factory where he applied for a job, he decided to go back to Fort Wayne.

One afternoon in early summer of 1965 I found my Mom sitting in front of her sewing machine, with a very sad look on her face. “I feel like crying because I have lost Alejandro. I sent him to Miami thinking that he would only stay a year and then he would come back to Cuba. But I don’t think that he will ever come back to us now. I have lost my child.”

To protect her child our Mom and Dad had made the great sacrifice that Cuban parents faced during those tempestuous times.

Let me back track.

On April 25, 1961, 8 days after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, Alejandro had been taken prisoner by the Castro police. The 15-year-old was detained for 12 days with a group of 13 or 14 men. On the afternoon of May 7, the militia men who were guarding them left the premises without giving them any explanations or any instructions about what to do. When one of the prisoners in the group decided that they should leave, they simply walked out. As I have written before, that was the event that triggered my Mom’s decision to persuade our Dad that all their children should leave the island.

Alejandro has told me that when our parents first broke the news to him that he was going to be leaving Cuba he was vehemently opposed because, without my parents knowing, he had just made plans to marry a girl named Marta. He also had a very strong feeling that if he left Cuba he would become a traitor to the counter revolution.

He spent several hours that night talking with my parents, set on his idea of staying in Cuba. After much discussion, and after talking with Marta the next day, he finally agreed to leave. Marta had found out that her parents were also going to send her away to Mexico. They also both thought that they would be back in Cuba in six months, since they were convinced the Castro regime would not last that long.

Alejandro remembers going shopping in downtown Havana for a shirt and a few other items with our mom and with Marta. He was told he could only pack a few things. He remembers his suitcase had 2 pairs of underwear, one shirt, a Physics textbook and a Geometry book. The Physics book by Alonso Acosta, was covered with a color page from a Spanish language newspaper. The Geometry book had the cover from his school, El Colegio de Belen, the school Fidel Castro had attended in the mid 1940’s.

On July 20th our Dad drove him at 6:00 a.m. to the Rancho Boyeros Airport in Havana. Only one person was allowed in the waiting room, and my parents agreed that Marta should be that person. At 5:00 p.m. he was taken out of the room. After answering a few questions, he was allowed to get on the plane. Alejandro and Marta corresponded for about six months. They never saw each other again.

Alejandro had taken the books out of his suitcase and carried them with him. He lost the suitcase, hence when he arrived in Miami he did not have clothes to change into. He still has the two books.

On July 23, three days after Alejandro had left, the G2 police knocked at our parents apartment looking for him. When they found out that Alejandro had left the country, they became irate. If he had not left Cuba, Alejandro would have been captured by the G2 again. My mom would have spent many years visiting her youngest son in a Cuban prison, if not the rest of her life mourning his death.

My parents were convinced that it was in retaliation for Alejandro’s departure that they and our brother Francisco Javier were not allowed to leave Cuba for a long while.

Let me get back to the summer of 1965 and subsequent years.

Towards the end of the summer of 1965 Alejandro married Judy, whom he had met in Fort Wayne, and they have lived most of their married life in the Midwest. They have two sons, Alexander Jr. and Derek, five grandchildren and one great grandchild. Alejandro and Judy always kept in touch with our parents. In our parents’ treasured correspondence I have found many letters, reports, photos and cards sent to them by Alejandro, Judy, Alex Jr and Derek. They visited each other in the summers, alternating between our parents travelling one year to see them in Indiana, and the next year Alejandro and Judy and children coming down to Miami to visit them.

Those visits were the highlight of my parents’ summers. When they visited Miami all of us siblings would get together in Miami. Our parents were the happiest when they were able to gather all their children in one place.

Thanks to the sacrifice our parents had made years before we were all able to partake many times in the joy of those recurring family reunions.

___________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

1 There were 41 Cuban boys at St. Vincent’s Villa in the early sixties. A group of them met recently. Here is a good article about their reunion.

Mass reunites Fort Wayne Pedro Pan refugees – Today’s Catholic (todayscatholic.org)

2 During his early years in Fort Wayne Alejandro officially changed his name to Alexander (Alex), and that is how most people know him. I kept the Spanish version of his name here for the sake of simplicity.

In memory of my oldest brother, Carlos Alberto Muller, July 14, 1935 – August 3, 2021

Less than a month after my arrival in Florida on July 5, 1961, my aunt Sarah and uncle Panchito received word that my brother Carlos Alberto and his wife María Antonia would soon be joining us in Miami. This gave me high hopes that I would be seeing them soon. I felt happy, looking forward to their arrival. The month of July ended and two weeks into August we still had not heard from them, or so I thought. In reality, Carlos Alberto and Maria Antonia had tried to leave the island but instead had been detained and my brother had landed in jail.

When my aunt and uncle received the news of my brother’s failed attempt at leaving Cuba and his detention they decided not to tell me then, even though they had received a letter from my Mom to me telling me all about it. They waited until he was freed to break the news to me and give me Mom’s letter. I was extremely sad when I read about their ordeal, and I was also upset that I had not been told about it before. “If I had known, I would have been praying for him,” I thought to myself. I have not found that letter from my Mom in my treasured stash of correspondence from those years. What follows here is based on my own reminiscence of it, on conversations that I had with members of the family and mostly from a digital draft of Carlos Alberto’s own autobiography that he had sent me not too long ago.

Allow me to rewind and start the story again.

On July 28, 1961, my brother Carlos Alberto and his wife María Antonia arrived at the Port of Havana to get on board the Joseph R. Parrot ferry, the same vessel on which I had travelled earlier that same month. They were confident that they would be allowed to leave the island since they had obtained a visa waiver to the United States. In addition, three days prior, in his July 26th speech, Fidel Castro had declared that even though there had been a rumor going around that he was not going to allow Cubans to leave the island after that day, anyone who wanted to leave Cuba was free to do so.

In spite of Castro’s July 26th declaration, Carlos was detained by G21 agents at the Customs Office at the Port of Havana. Maurice Dussaq, a friend of our family and an administrator of the ferries, gave orders for the ferry to wait until Carlos was released. After several hours it became evident that the G2 would keep Carlos from leaving on that day, and the ferry departed without him and without María Antonia. Although she was given permission to travel, she refused to leave without her husband. Both of them were detained and taken to the G2 headquarters on Havana’s Fifth Avenue. The G2 police released Maria Antonia that evening, but kept Carlos in the building’s small library (20’ by 20’) which had been turned into a makeshift jail holding 40 prisoners.

The room did not have enough floor space for all the prisoners to lie down to sleep. One of them slept standing up, leaning on the angle formed by the two walls on one of the corners of the room. When Carlos Alberto first arrived the police offered him the mattress of another prisoner who had died from diphtheria that morning while lying on it. Carlos refused to use that mattress and slept each night on the marble floor under another prisoner’s cot. There was one bathroom with two showers and one toilet. Infections were rampant under these unsanitary conditions.

Some of the prisoners had been members of the government police force and militia, giving rise to the suspicion that among the group there could be some government plants. Remy, one of the prisoners, would lead the praying of the rosary every night. He was a friend of our brother Francisco Javier and therefore recognized Carlos Alberto as being a trustworthy detainee. He delegated to him the task of leading the nightly rosary.

Carlos was released on August 12. As he headed home after having spent two weeks in the dark wearing only undergarments, his clothes felt uncomfortable and everything that he saw that had color, including traffic lights, grabbed his attention. In spite of the many precautions he had taken, he soon found out he had contracted an infection.

While Carlos Alberto was in prison the Revolutionary Government changed the Cuban currency making it practically worthless. When he and his wife were given permission to leave Cuba on October 4th, Maurice Dussaq, the administrator of the ferries, gave him the dollars necessary to buy two Pan American Airlines tickets. As Carlos Alberto put it, “having dollars to buy tickets to get out of Cuba was synonymous with having dollars to purchase freedom.”

Carlos Alberto had packed six books in his suitcase, and he was able to take three of them, because the lady who searched through his belongings at the airport was not a true revolutionary. Had that been the case, she would not have allowed him to bring any of the books with him. The three books reflected his interests and the person he aspired to be: an Engineering book that included a trigonometric formula that he was able to use years later while working as an engineer at the Bendix Corporation in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The second book was a philosophy book and the third book was a Spanish translation of the Four Gospels directly from the Greek. He had read the Gospel book several times during the worst moments of the years 1960 and 1961.

Carlos Alberto and Maria Antonia also took with them the maximum amount of money allowed by the revolutionary government: 5 Cuban pesos each. When they arrived in Miami Maria Antonia asked an unknown woman who just happened to be there to please give her a dime. With that dime she was able to call our uncle Panchito to come to pick them up at the airport. This time they had not notified any of the Miami relatives and friends of their trip. They were afraid that he would be taken prisoner again and for that reason they had kept their trip a secret.

For Carlos Alberto arriving at the Miami International Airport, fleeing from Fidel Castro, was one of the most incredible moments of his life. After all they had gone through he described feeling infinite peace and tranquility.

As they were settling in Miami, Carlos Alberto and María Antonia started their own family. I was a student at Ursuline Academy in Dallas, Texas and would spend the summers in Miami. One of the greatest joys I had during those visits was to meet my baby nephews, one by one, almost three summers in a row: first Carl Hans, then Carl Franz, and a few summers later, Carlos Alberto Jr.

Carlos Alberto enrolled at the University of Miami (UM) receiving his Bachelor’s degree in Engineering within a year’s time because he was given full credit for the three years of Engineering he had completed at the Universidad de La Habana. He became a professor at UM, a job he loved and held for several years. Besides providing for his young family he helped out many other family members as they first arrived in Miami and he also helped those who had stayed on the island.

Several years after he had bought his first home Carlos Alberto helped our parents buy their own house by co-signing on their mortgage. Decades later he also co-signed on our mortgage when we bought our home in Boynton Beach. On the day of the closing Carlos Alberto and María Antonia met us at the title company in Delray Beach. As they arrived he was smiling and enthusiastically said to me: “Elena, we have a home!”

Carlos Alberto died on August 3 at Hope Hospice in Fort Myers, Florida. He had celebrated his 86th birthday on July 14. We were able to visit him twice during his final days. One of the doctors at the hospital gave us hope that he would be ok. It was soon evident that his body was failing and could not endure the heart surgery that he needed. When he could only receive palliative care he was transferred to hospice and we also visited him there.

I am deeply grateful for the life of my oldest brother. In my mind I still see his smiling face and hear him say “We have a home!” I imagine him hearing similar words as he arrives to receive his eternal reward: “Carlos Alberto, we have a home for you!”2 I pray that he may now be experiencing in full the peace and tranquility of which he had a foretaste the day he arrived in his adopted country.

Carlos Alberto, dear brother, may you rest in peace in your eternal home.

Footnotes:

- The G2 is the main state intelligence agency of the government of Cuba.

- “In my Father’s house there are many dwelling places. If there were not, would I have told you that I am going to prepare a place for you?” John 14:2

When I was growing up in Cuba we celebrated Grandparents Day, el Día de los Abuelos, on July 26th, the feast of St. Joachim and St. Ann, the grandparents of Jesus. With the Castro Revolution, July 26th became the official day to celebrate the Movimiento 26 de Julio, the 26 of July Movement, one of several revolutionary organizations that fought against the Batista regime and the one that claimed triumph on January 1, 1959 after the dictator left the island. “Fidel spoiled our day,” I remember some grandparents complaining. Of course families could continue privately observing el Día de los Abuelos, but it was not the same.

Early this year Pope Francis instituted the World Day for Grandparents and for the Elderly on the fourth Sunday of July, the Sunday closest to the Feast of St. Joachim and St. Ann. It was celebrated for the first time yesterday. I am happy that the feast that we observed as children is now a worldwide celebration in the Catholic Church. On this occasion my thoughts turn to my own grandparents, long gone to receive their eternal reward. In a special way I remember my abuelita (granny) Antonia and the relationship she had with my mom, Augusta.

My grandmother, Antonia Bernabella Faife Rodríguez was born in Cuba in 1892. Her father was a descendant of a French family that had initially immigrated to Haiti and then had to immigrate to Cuba in the early 19th century during the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution. Antonia was married at a young age to José Asunción Mulkay Martinez. José, my grandfather was a doctor who sometimes would get involved in politics. His grandfather had immigrated to Cuba from Ireland, also during one of the Irish revolts. Augusta Eulalia Mulkay Faife, my Mom, was born in 1910, when Antonia was 18 years old.

Antonia and José had seven more children. I grew up hearing Mom telling me stories about her siblings. My abuela Antonia delegated much of the childcare to my mom, a role that she cherished. I was the beneficiary of Mom’s rich experience caring for her siblings, and then for my own siblings, since I was the last of four. By the time I was born Antonia was already a widow. I never met my grandfather José except in the many stories about him my mom shared with me.

When I was growing up my abuelita Antonia visited us frequently. She and my mom would spends hours chatting. Abuelita Antonia liked to travel and her favorite destination was Miami, Florida. My mom had never travelled. Before each of abuela Antonia’s trip she would make a list of things she would like her to bring. That was abuela Antonia – she would bring gifts from Miami not just for my mom and my siblings, but also for my aunts and uncles and my cousins. I remember her bringing me a pair of pink flip flops, the first ever flip flops I ever owned.

The Castro Revolution of 1959 changed everything. Abuelita Antonia, who had been an admirer of all things from the United States became a Castro sympathizer. My mom initially sympathized with the Castro Revolution, as did the vast majority of Cubans. Soon she started seeing that the Revolution was not delivering its promise of freedom and democracy, but quite the contrary. My mom, my dad and my siblings became counter revolutionaries. This caused tensions between abuelita Antonia and my mom.

On Sept. 2, 1960 I wrote a letter to my friend Ofelia who had left Cuba with her family and was living in Miami. I was 12 years old. Here is a translation of the original Spanish, without any added punctuation:

“Dear Ofe,

“Right now I am desperate. My grandma came and she just left because she just broke up with my mom because of Fidel. You know what that means that disgrace I do not know what I would do. My grandma said that “she could not stand the sight of priests” and that she did not need God. Mom begged her to stay that she should not break up with her family on account of FIDEL and his buddies….”

Mom and abuelita Antonia eventually set aside their political differences and made peace. After my mom and dad immigrated to the United States they stayed in close contact by letters, telegrams and phone calls.

When abuelita Antonia became terminally ill my mom was not able to travel back to Cuba because of government restrictions. One of my aunts who had remained in Cuba heard her call for my mom in her deathbed. “Augusta, Augusta, Augusta,” were her last words.

I recently told this story to an acquaintance. “What led them to reconcile?” I really do not remember how that happened, I just remember that at some point abuelita Antonia started to visit us again.

In our current society, here in the United States, I see families, close friends, colleagues, facing similar tensions in their relationships because of differences in their political views. I feel them myself. When that happens, the meaning of my mom’s words recorded on my letter to my friend Ofe, echoes in my mind: “Do not break with your family and with your friends because of politics.”