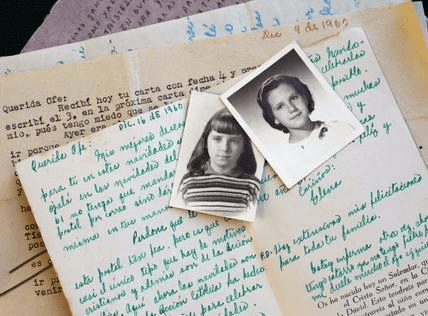

Ofelia (“Ofe”), my best childhood friend, left Cuba on the fourth of July of 1960, exactly one year before I did. She left with her mother, her two siblings and her grandmother. They travelled aboard the City of Havana ferry to Key West. Her father, who was already in Florida, met them there. Eleven days later I received a letter from Ofe to which I replied immediately, starting a correspondence between the two of us that lasted almost a year.

Ofe saved my letters. About twenty years later her mother, Ofelia, gave them to me. I stashed them away in a closet in my parents’ house in Miami. I did not read my letters to Ofe then and with the passing of time forgot about them.

In the Summer of 2009 I found the forgotten stack of letters. As I unfolded and read each letter I felt as if I had opened a window through which I was looking at my past. I read some to Sixto, my husband, and to my brother Javier. We laughed at the jokes I had shared with Ofe some of which were counter revolutionary and we marveled at some of the comments I had dared to write to her about life under the Castro regime.

In a matter of months I typed all the letters on my computer and translated them from Spanish into English. At present they are all printed and kept in a three ring binder with the title Saying Good-By to Havana. As I read them over again I realize they are just the letters of a 12 and then 13 year old girl going through adolescence and confiding in her friend: nothing remarkable. Throughout the letters, however, I included comments and reflections on how the Revolución affected our family, our friends, and our school. Here are some glimpses into my last year in Cuba, from July 1960 when our correspondence began through June 1961, when it ended.

On a letter dated July 15 I inquired about the feasibility of our letters remaining confidential:

“When you reply tell me if anyone else in your house sees the letters that I send you so that I know if I can write about other things”

On that letter I also wrote:

“From here I will tell you that I am resigned to receiving a Russian rocket in my arms, because when they launch it (if they launch it) towards the U.S.A. it could fall here because we are so close.”

The reference to Russian rockets might be puzzling since the Cuban missile crisis did not take place until two years later. However, since the 1950s rumors had already started about the possibility of a nuclear confrontation between the two superpowers of the Cold War. As Castro started to align himself with the Soviets the rumors came closer to home.

The closing of that letter was similar to the way I ended all subsequent ones:

“Good bye from your friend who loves you, does not forget you, misses you, and wishes to see you soon.”

On July 21 I guaranteed the confidential nature of our communications:

“No one reads my letters I have them very well kept in a place from which no one will take them so that you can tell me whatever you want in your letters.”

And then I went on to share a revolutionary joke. The parenthetical explanations are from the original letter. G2 refers to the Cuban General Intelligence Directorate or its agents.

“An American journalist interviews fidel ( lower case on purpose) and asks him when he plans to hold elections in Cuba and fidel answers. – Let G2 tell you.

“The American does not know what that means so he goes to a bar and asks the bartender. The bartender responds: — I do not know any other G2 than the one on the juke box (You know that in a juke box one presses a number and a letter.) So he tells the bartender

“–Look put a nickel in the juke box and press G2 to see what song it plays. The bartender does as told and the juke box plays. “More than a thousand years will pass… (It is the song “Sabor a Mi,”)”

I do remember that this was one of the many jokes making the rounds in Havana at that time. Humor has always helped Cubans cope. In January of 1959 Castro had promised to hold free elections. He postponed the elections at least two times. Unfortunately the joke became true. On May 1 of 1961 Castro declared that there would be no elections and there has not been free elections in Cuba in the past sixty years.

Here is a bit of political commentary that the 12 year old aspiring political pundit I was then wrote to Ofe on September 4:

“About Fidel and his buddies I have to tell you that Fidel is half crazy or at least he pretends to be (I believe that) since he does not even know how to count. At the last rally of stupid imbeciles and communists he said that there were one million people and with that he showed that the majority of the people were on his side in conclusion he said that 1 million was the majority among 6 million and it seems that that is a bit wrong, isn’t that true? I advise him to study his Arithmetic a little more.”

Sixty years later I apologize for the insult to the rally goers. I remember attending at least one of those rallies with my Catholic school, probably in early 1959, when my family still had hopes in the Revolution. I have memories of shouting slogans: Viva Cuba, Cuba sí, Yankees, no! Patria o muerte, venceremos! without really knowing the real meaning of what I was saying. And I pray to God that I never joined in a Paredón chant asking for enemies of the Revolution to be sent to the firing squad, a chant that was quite common at those mass gatherings. I became very cautious in participating in public demonstrations and that has been my wont throughout the rest of my life.

I am fast forwarding now to a letter I wrote on Tuesday May 2, 1961 during the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion when the Castro regime clamped down on the population and thousands of citizens were detained throughout the island, including my 15 year old brother Alejandro. As one would expect of twelve and thirteen year old girls, Ofe and I wrote to each other about boys. Ofe had just written me about a boy, and as I had promised I had put that letter in a secure place, not safe enough, however, to keep it from the milicianos (Castro police) who searched our apartment:

“Listen I tore up the letter where you tell me about the boy because I am afraid that if they come again to search they will read it. Did I tell you that they came to search Saturday before last at 2:30 in the morning. Imagine how sorry I feel for you because they read all or almost all the letters that I have and they must have surely read that one, but don’t worry because the miliciano that read them does not know you. But at any rate I tore it up just in case.”

Our house was not searched again and my brother Alejandro was allowed to come back home. Nevertheless, on May 25 I expressed my determination to leave the island at the first opportunity that would come my way:

“I really want to go there even though I know that I am going to miss mom and dad a lot and pretty Cuba but there I will be able to study and have the peace and quiet that is totally absent here, one day you wake up hearing airplanes and bombs. At night the gun shots from the accidentally discharged bullets and those fired on purpose don’t let you sleep, if you hear a car you think it is a plane, if it thunders, it seems like an air raid, a door that is shut hard sounds like a bomb and finally thousands of things that keep one in continuous shock.”

I have little doubt that I was showing signs of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when I wrote those lines. It is my non-expert opinion that all Cubans who lived through those turbulent times have been affected to some degree by PTSD.

I wrote the last letter to Ofe on June 17. I began the letter by telling her that rumor had it that after the 26th of July no one would be allowed to leave the island. The closing and postscript say it all:

“Your friend who loves you and really wants to go there,

“Me

“P.S. I have entrusted myself to all the saints so that I can soon go there.“

The rumor about Castro ending travel out of the island on July 26th turned out to be false, but I did leave the island on the fourth of July.

*Photo taken from “50 years later, ‘PedroPan’ children celebrate escape from Castro’s Cuba,” Palm Beach Post, Dec. 17, 2010. Lona O’Connor wrote the article. I cannot find the name of the photographer. Ofe’s picture is in the center, mine on the right, both on top of some of the original letters I wrote to her.

I spent my first summer in the United States in Miami. I stayed at my friend Ofe’s house and on weekends I would visit my aunt Sara and my uncle Panchito. I was getting ready to attend eighth grade at St. Theresa’s school in Coral Gables. Ofe’s mother, Ofelia, was lovingly getting the uniforms ready for me.

During that time I also corresponded with two of the nuns from Colegio de las Ursulinas, in Havana, where I had attended school for eight years. The school had been nationalized and the nuns had left Cuba, but I had managed to stay in touch with them. Just before the new school year started I received a letter from one of the nuns telling me that I had been given a scholarship to attend Ursuline Academy in Dallas, Texas. I told Ofelia and aunt Sara and uncle Panchito. They called my parents in Havana. My parents agreed to my accepting the scholarship and my going to Dallas, Texas. I don’t remember who paid for the plane ticket, but my next memory takes me to my first airplane flight ever.

The first letter I have in my collection is from September 6, 1961. I wrote it to my parents on that flight to Dallas. The thin white stationery on which I wrote in pencil has yellowed and there are several tears on the edges. The corners are dog-eared. There are several fold marks indicating the many times the letter has been folded and unfolded. Defying the passage of time, the cursive writing is still legible.

Here is a translation of a segment from the original Spanish:

“Dear papi and mami,

“Today I start a new adventure, which, God willing, will be for my own good. At this very moment I am flying through the clouds, I am thrilled because this is the first time I am riding on a plane, but every once in a while, as is happening right now, I wish I could see you, and since I can’t, my tears betray me. You know how much I miss you…”

What I did not tell my parents in that letter is what I had wished for just before writing it. This is a memory that I have carried with me since that day. As the plane took flight I was overcome by the realization that I was leaving behind my aunt and my uncle, my best friend and her welcoming family and that I was going to be even further away from my parents and my brothers. At that moment I prayed that the plane would fall in order to put an end to the extreme sadness I felt. That prayer lasted a nano second. I immediatley took it back. “No, Lord, I did not mean it. No please, don’t let the plane fall,” I prayed with all the strength of my soul. Luckily the second prayer was heard, and I arrived safely at Dallas Lovefield Airport that afternoon.

Carlos Eire, a most eloquent Pedro Pan, has written two memoirs, one of which, Waiting for Snow in Havana won the 2003 National Book Award. In his 2010 sequel, Learning to Die in Miami, death and resurrection is a theme that recurs throughout his masterfully written work. I experienced death and resurrection on that flight to Dallas. My death wished morphed into love for life, and thus I ended the letter on a cheerful note:

“Know that I am enjoying this trip. Mami, I think about how much you would like to ride on a plane, and you are right. I love you and remember you with all my heart, Elena”

That is one of many letters that I wrote my parents. Early on I asked them to save them and return them to me. They did just that and for that I am forever grateful. My collection also includes the letters that my parents wrote me as well as letters from each of my brothers and from some of my relatives. These letters kept me connected with them when I was thousands of miles away. Sixty years later the letters still connect me to my parents even though they passed on to eternal life more than a decade ago.

A week ago on a visit to friends in Altamonte Springs, Florida, I came across a news report about a new policy the Florida Department of Corrections (FLDC) wants to implement. It immediately caught my attention. In order to curb contraband, FLDC plans to digitalize all the correspondence that the inmates receive from their families and provide it to them only on tablets. At a hearing that was held on June 10th the relatives pleaded for that plan to be scraped arguing that the physical letters, the photographs, the drawings from their children are a lifeline to the inmates. “Handwritten letters are our hug, our touch,” one witness said. **

Siding with the relatives and friends of the inmates were federal public defenders and several organizations including some libertarian and conservative leaning groups and churches and ministries. If I had attended that hearing I would have joined my voice to theirs. I can attest that hand written letters are indeed hugs and touches when we are separated from those we love. And that is true even in this digital age.

_________________________________________________________________

* This photo is taken from Former Pedro Pan kids look back in exhibit. By Johnny Diaz, South Florida Sun Sentinel, July 1, 2015.

** “Letters are the lifeline”: Families plead for Florida prisons to retain physical mail. By Grace Toohey, Orlando Sentinel, June 11, 2021

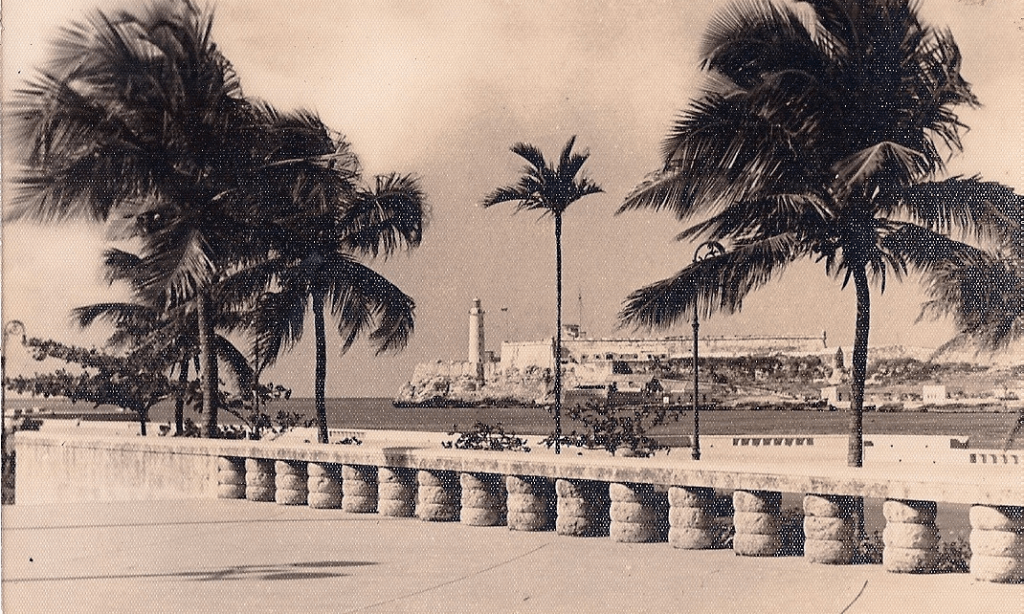

My Dad drove me to the Port of Havana the morning of the fourth of July, 1961. My Mom, of course, came along too. The Joseph R. Parrot was scheduled to leave at around noon. *

My parents were allowed to go up the ship deck with me and take a look at the cabin. It was a small cabin, and it had a small number of beds, 10 or perhaps 20? The ferry had been built in 1916 as a service vessel and had undergone various transformations. As a railroad car ferry it transported train cars filled with merchandise from the United States to Cuba and vice versa. Trade between Cuba and the United States had come to a halt and the ferry was now used mainly to transport people out of Cuba. There were certainly more passengers on the ferry than could fit in the cabin space.

Before my parents left back to the port they met a husband and wife aboard the ship. Although we did not know them, when they found out that I would be travelling alone they told my parents that they would look after me. I don’t think I ever knew their names and I don’t remember what they looked like but I do remember their presence and kindness.

A crew member told us that since there were so few beds, passengers would have to take turns during the night so that each one would have a chance to rest at least a few hours. Where I would sleep that night was of no concern to me at the time. My biggest concern was to take a last look at the island as the vessel sailed away from the bay of Havana. I rushed to get a good spot on the deck, by the ship’s railing. As the ship left I waved good bye to my mother and father. Long after I could no longer see them, I continued to look at the Morro Castle, my last view of Havana. The plan was for me to spend about one year in the United States where I could safely attend school and then return after the certain fall of the Castro regime. Nevertheless, I wished to have that image of the bay of Havana seared into my heart.

I remember the blue ocean, the blue sky, and the sun. I remember eating dinner that 4th of July in a small dining room that had a long table. I ate several slices of white American bread with butter. Although food was not yet rationed in Cuba, the quality of most foods had deteriorated. This first meal was a delicious treat. There were other people sitting at the table and although time has erased any memory of what they looked like I do remember that they were nice to me.

After the meal, I returned to the ship’s deck. I stood by the railing again, this time to watch the sunset at the sea. One of the members of the crew approached me and struck a conversation with me. I was elated that this handsome man would talk to me. He went on to talk about his wife in Miami. “I have some friends that I would like you to meet,” he said. He wrote his name and phone number on a piece of paper and gave it to me. After he left I reflected on what he had just said. I tore up the paper and threw it away.

Although my intention was to stay awake all night I eventually felt exhausted and had to take a turn at one of the beds in the cabin. The ship’s old machinery was right next to the cabin, or so it seemed. The noise kept me from falling asleep. I got up early and watched the sunrise.

Breakfast was as delicious on the morning of July 5th as dinner had been the day before. I drank white milk and liked it for the first time in my life. Regular milk had never tasted good to me. My mom always prepared our morning “café con leche” with reconstituted condensed milk.

The J.R. Parrot arrived in Palm Beach at noon. Elenita, a friend of our family who resided in West Palm Beach, came to meet me at the port. She bought me a Coca Cola from a vending machine. Coca Cola had been available in Cuba, except during the last few months. What a treat that was! And it was the biggest Coca Cola bottle that I had ever seen. To my surprise, I drank it all.

After a short visit at the friend’s home, one of her relatives, also named Elena, drove me in her car all the way down to Miami. It was a long road trip. I marveled at the wide highways with so many lanes.

We arrived at the home of Graciela and Ectore in Miami, close to dinner time. Graciela was my aunt Sara’s niece. At the time, a total of 14 people lived in their three bedroom house. I think that the main course for dinner that evening was meat loaf. I savored every bite.

After dinner Graciela and her sister, also named Elena, and her two daughters Georgina and Gracielita invited me for a walk to the nearby shopping center. I agreed. I was completely astonished by the Walgreen’s and the dime store where we went that evening. It was still daylight.

While at the dime store I needed to use the bathroom. I was puzzled when I saw that there were two bathrooms and two water fountains. One was labeled “white” and the other “colored.” Noting my hesitation, my companions gave me a brief explanation.

On the way back from the shopping center the experience of the two days shook me up from inside. As I felt a sudden jolt of homesickness, I made a great effort to hold my tears. “I can’t go back,” I said to myself. It was not long roads that separated me from my parents and brothers. It was the vast ocean that I had seen during the long night at sea that separated us, and no matter how I felt, there was no immediate way back.

I remember that moment as the time when I grew up. In one instant I ceased being Elena the child. I had left my parents and brothers behind. I became Elena, the no longer child. I succeeded in repressing my tears so no one noticed.

We continued our walk until we reached Graciela’s house where I spent my first night in the United States.

—————————————————————————————————————–

*People ask me: “Didn’t all Operation Pedro Pan children leave Cuba by plane?” Yes, 99.9% of Pedro Pan children travelled by plane to the United States. A few of us came on the ferry. I happen to be one of them.

This coming July 4th will mark the sixtieth anniversary of the day I left Cuba, the island nation where I was born and where I lived for the first 13 years of my life. I came as an unaccompanied minor, leaving behind my parents, my siblings and life as I had known it.

Initially, my family supported the Cuban Revolution. A few months after its January 1, 1959 triumph, however, my family realized that this was a communist revolution, not a pro-democracy, pro social justice movement. The promise of freedom was soon shattered as anyone who questioned the measures being taken by the Revolution was dubbed an enemy of the people, un gusano, a worm. The Revolutionary government started sending people to the paredón, the firing squad, without due process.

At first I did not want to leave the island, much less without my parents. I held to the hope that military action taken by Cubans who had left the island and supported by the United States would free us from the oppressive Castro regime. In April, that military action, the Bay of Pigs invasion, failed. During the ensuing days thousands of Cubans were imprisoned by the regime. My then 15-year-old brother, Alejandro, was detained for two weeks. For my Mom, that was the tipping point. “I tried to keep my children safe and they took my Alejandro,” she wrote me two years later, explaining her decision to convince our Dad that they had to send us away.

When my Dad agreed with my Mom that it was best for us to leave the island if we could, I too was ready to leave without them, or so I thought.

On July 3, 1961 my Mom told me that I had been given a visa waiver to travel to the United States through “that which is called Operation Pedro Pan.” I left on July 4th aboard the Joseph R. Parrot a train ferry that plied the waters between the Port of Havana and the Port of Palm Beach, where I arrived on July 5th. I was to stay with my best friend and her family who had arrived in Miami a year earlier.

People ask me: “What was Operation Pedro Pan?” Operation Pedro Pan was an organized endeavor of the United States government, the Catholic Church, and some concerned people in Cuba that made it possible for parents who could not get permission to leave the island, to send their children to the United States to keep them safe from the Castro regime. More than 14,000 Cuban children arrived in the United States, unaccompanied, from December of 1960 through October of 1962 thanks to Operation Pedro Pan.

People also ask me: “Were you reunited with your family?” Yes, within a year my three brothers arrived, separately, in the United States. It took my parents three years to get permission from the Cuban regime to leave the island. We were reunited in Miami in June of 1964.

Today people ask me: “What do you think of the arrival of thousands of unaccompanied children through our Southern border?” Although the particular circumstances differ, ultimately they are arriving here for the same reason that I came 60 years ago: seeking safety and an environment where one can thrive. Undoubtedly, it was emotionally taxing and I faced difficulties as an unaccompanied child. I also experienced the kindness of friends, extended family and generous Americans who cared for me. My wish is that today’s unaccompanied minors, who in the whole experience greater trauma than I experienced, may receive the kindness, love and generosity that allowed me to thrive in this country.

Sixty years ago I embarked on a new path that changed my life forever. Leviticus 19:34 compels me to treat today’s foreigners with love, as I love myself and as if they were native born, because I was once a foreigner myself. It is in obedience to that commandment that I hope to live the remaining years of my life.

Recently I had lunch at a restaurant in Miami with four of my former classmates from Colegio de las Ursulinas, That is the school I attended in Havana starting in “Pre-primario”, a grade between Kindergarten and first grade, until the first year of “Secundaria Básica,” the equivalent of seventh grade. Some of us had become friends at age six, and attended school together until we turned thirteen.

Four of us, Ofelia, Gilda, Silvia and I, currently reside in South Florida. Teresita resides in New Jersey, and was visiting in Miami for a week. We had not seen her since our school days in Cuba. Of the five of us, Teresita was the one who arrived in the United States from Cuba the latest – in 1994. The rest of us left Cuba during the first years of the ill-fated Revolution.

A little over a year ago Teresita sent me an e-mail – her daughter had been searching for her Mom’s schoolmates in the internet, and managed to find me. What a joy and a surprise to hear Teresita’s voice then and during subsequent phone conversations. What a greater joy to finally meet her in person again – 52 years later.

As our conversation turned to our lives after we left the island, each trying to cram more than 50 years worth of experiences into a few short hours, our friend Silvia suggested that each one of us write what we think our lives would have been if there had been no Revolution. A school teacher by profession, turning the restaurant where we were sharing a lunch of croquetas, plantains, rice, black beans and other Cuban fare, into a classroom, Silvia challenged us to get paper and pen and write about “What If?” Write it when you are home, she said, and let’s compare notes by e-mail afterwards.

I generally do not like to think about how things could have turned out differently. Silvia’s question, however, has been resonating in my mind. It has led me to indulge in imagining how things could have been, for me, if life in Cuba had not been disrupted to the core on January 1, 1959.

During the years just before the Revolution, my life pretty much was centered on my family, my friends, and school. In school I was involved in the “Acción Católica” (Catholic Action) children’s groups. At home I was the youngest child and the only girl. My brothers Carlos and Javier had graduated from Colegio de Belén, the largest Catholic school in the island, and Alejandro was attending “Bachillerato” there. Carlos was already married, was a teacher at Belén, and attended the University of Havana whenever it was in session (most of the time it was closed due to the political unrest.) My brother Javier attended the University of Villanueva.

I imagine that I would have graduated “Bachillerato” at Colegio Ursulinas and, following on the footsteps of my brothers, and of both my parents before them, I would have continued to study at the University of Havana, or perhaps Villanueva. Since we lived within walking distance of Belén, I imagine I would have married a boy from Belén, most likely a boy from my brother Alejandro’s class. I imagine myself as also continuing in the Catholic Action groups, moving on into the university student group, and eventually into the adult group. I have a lingering memory of the day I used two strips of red tape to make a cross on the side of my brown book bag as I said out loud: “I am going to be a missionary in Africa.” So that, too, is a path I might have taken.

The “what ifs” could continue on for pages, so I am right now putting a halt to it. The Revolution happened, and as a result, so much that could have been did not come to be.

When I compare my life as I have actually lived it with the many “could have been” I realize that the seed that was planted in my early childhood by my family and by my school, did come to fruition: not only did I graduate from high school, I graduated from an Ursuline high school in Dallas, Texas. I attended three universities and completed a Master’s Degree in Religious Studies. I have worked in some capacity or another in Catholic institutions almost all my working life. And although I did not marry a boy from Belén, my husband, who is also Cuban, was a member of the last graduating class of La Salle, another prestigious all-boys Catholic school in Havana.

The difference in the “what could have been if” lies not so much in what I have done, it lies on the crucial fact that all that I have done I could have done in Cuba speaking Spanish only, and because of the Revolution, I have done it all in the United States, speaking English. The big differences: the place and the language. Though I feel blessed that I was able to learn English and am forever grateful to my adopted country, my heart bleeds for the Cuba that I could have helped build and for the church in Cuba to which I could have contributed. Even a deeper hurt is the memory of my parents, and the members of their generation who came into exile, who lost everything for which they had worked, including, in the end, the hope of ever returning to their native land.

In 2009, a series of unrelated events led me to reexamine and reacquaint myself with my Cuban past. The journey has been exciting, joyful, as well as sorrowful. It has also led me to harbor, once again, the hope that my parents lost. I have come to believe that it is still possible that in Cuba what could have been if, will be, before the end of our own lifetime.

A Cuban friend of mine compared the current proposals for gun control to Fidel Castro’s government taking of all the weapons owned by Cuban citizens at the start of the ill-fated Revolution in 1959. I strongly disagreed. “There is no comparison,” I told my friend. “The circumstances are completely different,” I reiterated.

We were both shocked: he, because I did not agree with him, being that I am Cuban, and lived through the first two years of the Revolution; I was shocked because the complexity and horror of the Cuban Revolution is so greatly minimized when we compare it to the situation in the United States today.

Unfortunately, the comparison keeps popping up here and there, and instead of shedding light on finding a way to halt the spread of the current epidemic of horrific violent crimes committed with the use of guns, it only adds more confusion. For those who believe it, the problematic then becomes one of state versus individual rights, of government versus the constitution, of citizens defending their first amendment rights from rulers seemingly intent on conducting a power grab.

And that takes us away from the heart of the problem: What on earth is the evil force that led an Adam Lanza and a Nehemiah Griego to use the lawfully owned guns of their own parents to kill their own mothers, and then in the first case, kill innocent children and teachers at an elementary school and in the second case, his own younger siblings and his father? As we seek to identify the monster that seems to be lurking in our nation before it strikes one more time, what is wrong with trying to put some restraint on the deadliest of assault weapons that in the wrong hands can produce a massacre in an instant?

Bringing Castro’s speeches and actions of 54 years ago into the mix of the discussions and debates of the current epidemic of violence that assails us, adds monsters that were instrumental in the Castro power grab of my native country then, but that have nothing to do with the demons that are lurking in my adoptive country now.

The Castros are still causing havoc in Cuba and in Venezuela. When it comes to the evil that is assailing us here in the United States, the culprits will not be found there.

A Cuban’s Lament

My father, Carlos Antonio Muller, wrote this poem, in Spanish*, in November, 1963. At the time my three brothers and I were already in the United States. My father and my mother were still in Havana, Cuba, where they had been waiting for more than a year to receive permission to leave the country.

To those who enjoy

the blessings of liberty,

with its carols and its joys

comes the Feast of the Nativity

The Feast of the Nativity is near!

And, with it, the Redeemer

bringing joy to the whole world

with His glory and His love.

How much joy is for the taking

if we have liberty!

If we can all gather together

to celebrate the Nativity.

How much Christians do rejoice

with the Feast of the Nativity!

When the God Child brings

the greatest festivity.

Liberty and the Feast of the Nativity!

O what ineffable delight

when we finally gather

with the people we love . . .

Liberty, how beautiful the sound

of such wondrous words

ever filling the soul

with peace and with hope.

Feast of the Nativity! God bestowed on you a very special power

to lift our humanness

to new spiritual heights.

Nativity and Liberty!

How many doubts assail us

when those who are dearest

are far away and missed.

How can other nations

enjoy peace for even a second,

while those of us dwelling in Cuba

are forgotten by the world?

No one feels compassion!

Why? Seeing our affliction

from this terrible oppression

living in the grips of fear?

How much sorrow abounds in my Cuba

during this Feast of the Nativity…!

Will our friends not come

to restore our liberty…?

They must have hearts like rocks

those who are blissfully happy

and are blind… and are deaf

to our wretched laments.

Liberty… given by God

as a gift to all humankind,

if you are absent . . .what great sadness

when the Nativity arrives!

Feast of the Nativity! May your holy name move other nations

to make it possible that in my beautiful Cuba, liberty will once again arise.

Feast of the Nativity! May in your name

PEACE return to us,

and free my fatherland

from this treacherous regime.

Why post this 49 years later? First, because Cuba is still a nation in chains, and, sadly, to a great extent, the world still seems to ignore this fact. Secondly, because as we approach the celebration of Christmas, I still harbor my father’s hope that peace and freedom will be restored in our country of origin.

*I thank my brother, Francisco Javier Muller, and my husband, Sixto Garcia, for their help with the translation into English.